The Great Dismal Swamp loomed large in the fervid imagination of the young Weazel. I was fascinated by the fact that it was great and dismal, and most importantly, a swamp. A swamp is more than just a forested wetland. A swamp is a place alien to man, a place of mystery where there are denizens, not inhabitants, and where the denizens lurk rather than dwell. A place full of snakes.

(A note to my faithful readers: This post is somewhat longer than usual. According to AI, the average dunderhead can read this in exactly one hour. If you are capable of watching a TV show uninterrupted for one hour, then you should be able to read this in its entirety. Please do.)

Where to begin? One of my earliest memories was of my mother using modeling clay to create crude facsimiles of animals. She wasn’t much of a sculptor, but her lumpy little representations of snakes and turtles fired my imagination. In my mind, I can still see that little clay turtle. Mom got it right with both carapace and plastron. Since then, there has never been a time when I did not keep snakes, turtles, and other reptiles, the pursuit of which has driven the trajectory of my life, and led to wondrous adventures around the world.

Concurrent with my burgeoning interest in nature was what appeared to be an inborn affinity for the south. At the time, Mom and I lived in Arlington Virginia, which is just across the river from Washington, D. C. Our neighborhood, Rosslyn, is now a highrise hellscape of office buildings, but during the mid 50s it was an interesting but dilapidated multicultural suburb of mid 19th century vintage which was imbued with southern history. The Potomac river, not the Mason Dixon line, was what separated north from south.

I absorbed southern heritage as though by osmosis, this despite the fact that my mother was an early feminist of liberal persuasion who had not a trace of a southern accent. She taught me enlightenment values, which, despite what you may think, I retain to this day.

We visited historic sights like the Capitol and Mount Vernon. History was everywhere I looked, from commemorative plaques to statues of heroes. The past was alive, and it was impossible not to take sides.

My inchoate opinions slowly coalesced into a sort of agrarian romanticism.

My inchoate opinions slowly coalesced into a sort of agrarian romanticism. I admired the grounds of Mount Vernon where George Washington plotted to form a new nation. I was overwhelmed by the grandeur of Robert E. Lee’s mansion, and by the beauty of the Virginia hunt country where the wealthy lived and sported like English lords.

Though we ourselves were poor, I identified with the long gone southern gentry who lived in pillared mansions and sipped mint juleps on the porch while discussing literature and horse flesh. I had never met such people, but I instinctively knew I was one of them. Such a lifestyle seemed to me to be the epitome of civilization, the natural order of man. Meanwhile, happy darkies toiled in the fields.

Courtesy Charlottesville Equestrian Properties

As for actual black people, they were irrelevant. I had been taught to be respectful to them as a form of noblesse oblige. I was kindly disposed to the few rural blacks I met, they seemed genuine in a way that others did not, and were invariably friendly. It was obvious to me that urban blacks were different, they were dangerous, degraded, and needed to be avoided. I was greatly confused to meet several real Africans on the Mall who were clearly superior individuals. They were jet black, not brown, spoke crisp English with a funny accent, and had impeccable manners. It only later occurred to me that they were diplomats.

In contrast to all that were the damnable Yankees who lived just across the river. We (notice I am saying “we”) were men and women of honor who valued our blood, our soil, and our traditions, whereas they (them, the others) were an alien race of invaders, scalawags, and carpet baggers who used the law to their advantage, but knew nothing of place or honor.

Yankees were rootless people who worked in offices and lived alienated lives in identical suburban houses and apartments. They didn’t know their neighbors. I watched in horror as their toxic culture, spread through the mediums of television and subdivision, crept across the land devouring all vestiges of grace, beauty, and nature to leave behind nothing but a homogenous landscape devoid of life. I hated them.

Yankees were rootless people who worked in offices and lived alienated lives in identical suburban houses and apartments. They didn’t know their neighbors…I hated them.

So it was that I was disposed to go south, not north. Imagine my dismay when we moved to Maryland.

………………………………………………………………

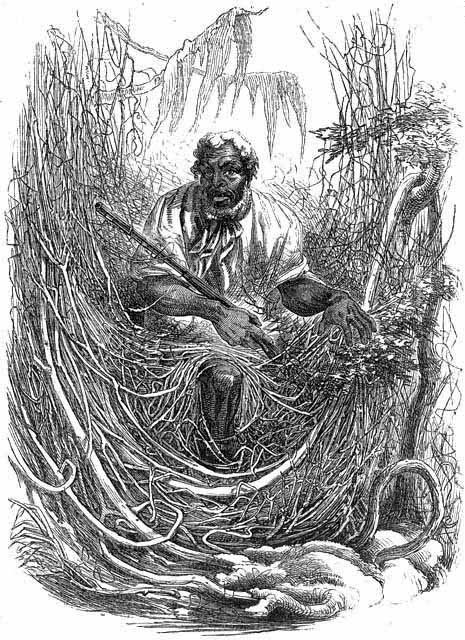

The primeval swamp

By my middle teens I was already a well traveled young man. By that time I had hitchhiked many hundreds of miles, and did so on a regular basis. Such a feat was made possible by the indulgence of my sainted mother who encouraged my wanderlust. Though exhausted from working as a single mom, she would return home at the end of a long day to wonder where I was, and to await the call. “Hi Mom. I’m in West Virginia (A different State). Can you come get me?” So perhaps it was out of self preservation that she gave me a car shortly after I turned sixteen. One of the first things I wanted to do with my newfound mobility was to go to a real southern swamp.

There are many sorts of swamps around the world, but in the southeastern US the most iconic of all is the cypress swamp. Just picture any horror movie you might have seen featuring snakes and alligators. The water is still and black. From it rise the ancient boles of cypress trees, Taxodium distichum, along with their gnarled roots known as “knees”. From the limbs above hang tendrils of moss, gray phantasms drifting in the mist. The bloop you heard was probably a reptile!

I’ve always been interested in biogeography, and can pour over maps for hours. I knew that the southeastern US was one of the most snake infested places on earth, and that the biggest and best snakes, the ones I most wanted to catch, lived in or near cypress swamps.

Family lore showed me the way. I am descended on my mother’s side from a long line of itinerant Methodist circuit preachers who roamed all over rural North Carolina preaching a gospel that today would be considered something close to liberation theology. My grandfather was very liberal, a free thinker who was not afraid to tell the inhabitants of small southern towns that they were hypocrites. So it was that they were thrown out of town after town.

Each posting was worse than the last. By the time they got to Old Trap in northeastern North Carolina Granddad’s faith in God’s beneficence was wearing thin. They were surrounded by swamps, and by the lowest sorts of indigenous white trash. My poor dim witted grandmother, who was both ignorant and bigoted, lived in terror. If you live in a swamp it eventually seems normal, but what about the big bad swamp just beyond the known zone? The one they tell the tales about?

In a time and place with no electricity women in such remote villages gathered to gossip. After church, my grandmother heard dark tales of the great swamp not too many miles away, of the ghosts, Indians, and runaway slaves, and of the fools who entered, never to return. So it was that many years later those garbled legends were passed on to me. It was a place I had to visit.

…………………………………………………………………

Maroons

The Great Dismal Swamp is legendary, not just because of its impenetrable nature, and reputed denizens, but because of its place in American history.

Indigenous Americans were said to inhabit the swamp, but I think that unlikely given that there were better places nearby. Archeological evidence indicates that they visited on hunting forays, but probably never stayed.

Some of the earliest English attempts at colonization were along the eastern seaboard in places like the doomed colony of Croatan on the Outer Banks, and Jamestown in what is now Virginia. Both are quite near the great swamp, which impeded expansion into the fertile grounds further west.

In 1728 while surveying the Virginia-North Carolina border William Byrd II found the place “dismal”, and “a miserable morass where nothing can inhabit”, hence the name.

Slavery, the preferred economic model for development throughout the early south, worked best in places where the slaves couldn’t escape. The great swamp originally covered over a million acres, more than enough room to hide an escapee, so those with the initiative to do so fled to the middle of nowhere. They were joined by the few remaining Indians, and by white desperados running from the law. Lake Drummond in the center of the swamp became an outlaw community, the black inhabitants of which were known as Maroons.

In 1842, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow had this to say:

In dark fens of the Dismal Swamp

The hunted Negro lay;

He saw the fire of the midnight camp,

And heard at times a horse’s tramp

And a bloodhound’s distant bay.

Where hardly a human foot could pass,

Or a human heart would dare

On the quaking turf of the green morass

He crouched in the rank and tangled grass

Like a wild beast in his lair.

Those freemen who could safely trade with outsiders made a business out of cutting shingles from the vast forests of Atlantic white cedar Chamaecyparis thyoides that dominated the wet but not submerged parts of the swamp. Like Cypress, the Atlantic white cedar is a tall straight tree, the wood of which is extremely resistant to rot. Due to straight grain it was easily split into shingles which were in great demand. Contemporary historians often claim that the draining of the Dismal Swamp was for the benefit of agriculture, but I believe the main incentives were to recapture slaves, and to commercialize the vast stands of Atlantic white cedar.

In 1763 George Washington and others formed the Dismal Swamp Company with the goal of “draining Improving and Saving the Land”. The idea was to use slaves, but they kept escaping. Growing hemp was another of their goals (Note to growers: Dope doesn’t grow in acidic swamps!)

When all that failed our ever enterprising first President decided to use Dutchmen instead of slaves. That failed too. In 1793 he joined with notorious patriot Patrick Henry to create a canal through the swamp that would enable inland transportation from the Chesapeake Bay to Albemarle Sound. It was completed in 1805, but was still unprofitable. That left only one thing to do, cut the whole place down.

The forest was destroyed, and canals were cut, but they never succeeded in draining the Great Dismal Swamp, which remains a swamp to this day.

Nothing happened after that until the 1930’s when old Route 17, the King’s highway, was built along the eastern edge of the swamp. For me it was a road of destiny because it was the road that first took me south.

………………………………………………………………

Monsters of all sorts

In 1964 my snake hunting buddy Dave and I joined an older fellow named Rick on our first trip to the swamp. I rejoiced when we crossed the North Carolina line. I was home at last!

Right away I found my first kingsnake by the side of the road. I was ecstatic! The noble kingsnake is one of the most iconic reptiles of the deep south, a powerful predator capable of killing and eating even the formidable water moccasin. Thus began a lifelong love affair. Even today I am a slave to the kingsnakes that live on my back porch.

It was a good start, but shortly thereafter we found a monster that defied all expectations. In a cutover cypress swamp with water about six inches deep we beheld a behemoth. Something enormous was slithering through the swamp with its back half out of the water. We supposed it was a huge moccasin so, with great trepidation, we charged headlong into the swamp. It proved to be a fish, so Rick threw himself on it and a great battle ensued.

When it was on dry land I gaped in astonishment. My first thought was that it resembled a coelacanth, one of the oldest living creatures on earth with a lineage extending back more than 410 million years

As a junior know it all naturalist I realized that it was a bowfin Amia calva, also known as the mudfish, but this was no ordinary fish. It was clad in armor, at least three feet long, and probably weighed thirty pounds, bigger than the current world’s record. I had never seen, or even imagined, such an ancient creature. It was like meeting a dinosaur.

Bad analogy. The bowfin has been around for 250 million years, older than the oldest dinosaur. I carefully examined its huge bony head. It appeared to be effectively toothless like a large mouth bass, so I presumed that to be a trait of the species. We released it to live another century or two.

It was a short trip, but I was hooked. The following spring I returned to the swamp with my friend Pete. We were equipped with a dip net, seine net, and buckets to collect aquatic creatures for my aquaria back home.

The vegetation choked water was full of life! There were many species of sunfish including bluegills, pumpkinseeds, redbreasts, fliers, and tiny blue spots. They glittered like jewels as they jumped about in our nets. There were mad tom catfish, darters, and minnows. Best of all were the sleek little pickerels that to me looked like tiny barracudas.

Every dip brought up an abundance of crayfish and aquatic insects. Most impressive were the giant “toe biters”, fearsome predaceous water bugs which we imagined would swim up our pant legs as we waded through the slime. (It could happen!) They are so big that they kill and eat small vertebrates. The bite is horrific.

Unfortunately, all of these wondrous creatures met their demise either on their way north, or shortly after I arrived back home.

While netting up this incredible abundance we caught a young bowfin about 14 inches long. I was an expert, so to demonstrate my knowledge I said, “They have no teeth”, and stuck my fingers into its mouth. That was a big mistake! The giant we had previously caught was so old its teeth had fallen out, whereas this one was in the prime of life. It did its best to bite my fingers off.

While thrashing around in waist deep water being bitten by bugs and a bowfin I failed to notice that I was dangerously close to my first moccasin!

……………………………………………………………….

Meet the mighty moccasin

Allow me to digress to sing the praises of the much maligned moccasin. The water moccasin Agkistrodon piscivorus, AKA Cottonmouth, is one of North America’s most feared reptiles. They are big, mean, ugly, and common throughout their range, the northernmost extent of which is the Dismal Swamp.

A few have been found in nearby Virginia, but if your granddaddy tells you a story about a moccasin north of there, or somewhere in the mountains, then he was either wrong or lying. I once got into a fistfight with a kid who insisted that his uncle was killed by a moccasin in West Virginia. Knowing more about science than other kids isn’t a good way to win friends.

Another common misconception is that they are aquatic. It is true that they are most common near water, but like the proverbial 800 pound gorilla it goes wherever it pleases. I have often found them far from the nearest swamp.

Every Redneck believes that moccasins dwell in trees along the shoreline and jump into boats to attack innocent fishermen, thus necessitating the blowing of a hole in the bottom of the boat with a shotgun. When that happens the boat sinks and the hapless fisherman is set upon by a “ball” of moccasins.

Some years later I was exploring a creek in southwestern Alabama with a friend who was the owner of a punk rock club. He had never even seen the sun, much less a moccasin. He asked me about the deadly snakes that jump into boats, whereupon I explained that those were harmless water snakes. Moccasins stay on the ground and never climb trees. I was explaining all this when I heard a branch break high above me. I instinctively flinched which was a good thing because a gigantic blond moccasin fell out of the sky and landed with a thud at my feet. Needless to say I had to pick it up.

The moccasin is closely related the the smaller more attractive copperhead which lives throughout much of eastern North America, and is very common along the periphery of the swamp. The young of both species are almost identical. Both are venomous, but moccasins are much larger, the venom is more potent, and they are more inclined to bite.

In the bad old days if a person was bitten by a moccasin they were likely to lose the affected limb, or die. You might think that would be enough to dissuade me from picking one up, but no. Now, back to the swamp.

………………………………………………………………..

My first meeting with the Judge

We were busy seining up swamp monsters when suddenly we beheld our first moccasin coiled up on a half submerged log. We had been close to it but had failed to notice. Much excitement ensued as we used our snake hooks to fling it ashore. With great trepidation I pinned its head, and with Pete’s help stuffed it into a bag. After the excitement died down we looked around for more and were astonished to realize that they were all around us!

We caught several more. One might reasonably ask what we were going to do with them. My mother strictly forbade any venomous snakes at home, so the plan was to sell them to the Catoctin Zoo, a roadside snake farm in Maryland. The going rate was $1/pound, not nearly enough for catching a snake that wants to kill you. It was a fate worse than death for the poor moccasins. They were thrown into a concrete snake pit so tourists could gawk, there to slowly die.

We were elated by our success, so it was time to celebrate! At the end of the day we drove to the nearly little town of South Mills NC on the southern edge of the swamp in search of dinner. Hurdle’s Restaurant was the only place in town.

In the corner sat a hideous creature who resembled Jabba the Hutt. “Judge” Hurdle was enormous. His neck was much larger than his head, and featured rolls of red flesh. I had heard the term Redneck before, but had never actually seen one.

We all stared at each other in mutual astonishment, then he asked, “Are y’alls boys or girls?” (Y’alls is the plural of y’all, which, though seemingly plural is actually singular.)

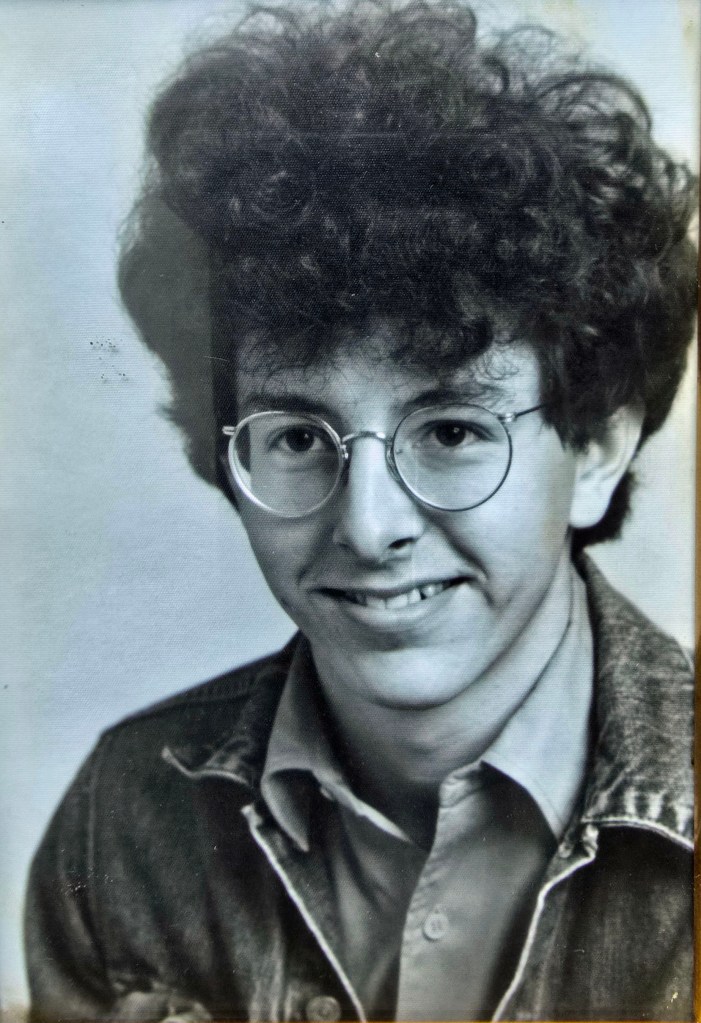

At the time I had a big curly “Jew-fro”, and Pete looked like a skinny girl with long blond hair.

He was clearly confused, for he had never seen Hippies before. At the time I had a big curly “Jew-fro”, and Pete looked like a skinny girl with long blond hair. I loudly answered, “We are men, Sir!” “Then why in Hell do you have long hair?” It was a legitimate question which we tried, and failed, to adequately answer. He had heard of Hippies, and of their objections to the war in Vietnam, so he conflated them with communists. I asked him what he thought a communist was, and he replied, “Anyone we don’t like around here!”

Despite the culture clash he seemed fairly reasonable. He asked, “What brings y’alls to these here parts?” “We are here to catch snakes, Sir.” I proved it by bringing in a bag of snakes. “But why?” “So we can sell them to Yankees!” He liked that thought, then asked how much they were worth? I told him, and he was unfazed by the ridiculously low price. “Why shee-it Son, we’ve got us plenty of moccasins around here!” I could see the little cash register widgets going around in his eyes. “How about we go out tomorrow and catch us a bunch?”

Thus began one of the strangest relationships ever. Extremely liberal Yankee Hippies from Washington, D.C. had made friends with the head of the local Klavern of the Ku Klux Klan! We knew nothing of that at the time, and he never spoke a word about it until much later. Much of what we later learned was from his family and friends.

……………………………………………………………………

Git on in there Boy!

After a miserable night of sleeping under a bridge on old Rt. 17, during which we listened to the trucks rumbling overhead, and tried to ignore the snakes, mosquitos, and spiders, we met Judge Hurdle for breakfast. (This was before I knew how to camp) With him was his retarded son.

The Judge described having seen great slithering clusterfucks of snakes just a few days earlier.

We climbed into a small motor boat, then headed up the canal and into the swamp. The Judge described having seen great slithering clusterfucks of snakes just a few days earlier. These must have been mating events. At the northern extremity of their range moccasins behave more like their viper relatives such as copperheads and rattlesnakes which congregate to hibernate (brumate), then emerge to mate. Moccasins are sexually dimorphic, males are much larger than females, and they wrestle for dominance. It is a lively affair which must have so impressed the Judge that he supposed he could make money catching them at $1.00 per pound.

We saw no snakes whatsoever. As we turned up a small creek we could not help but notice the gathering storm. I had never been around a retarded boy before, but it was clear to me that he possessed a terror of the storm not unlike that of a dog. With every crash of thunder I saw the whites of his eyes as he cowered low in the boat. It was almost as dark as night, and all around us trees fell with a mighty roar. The Judge was unfazed, and I was having fun!

The swamp closed around us until the way forward was blocked by a sodden floating log covered with ferns and moss. The Judge rammed it with the boat. It would move, but not enough. He turned to look at the boy, but said not a word. The kid may have been retarded, but he knew what was coming next. He cried, “No Daddy no. Please don’t make me do it Daddy!” After a long silence punctuated only by thunder the Judge said, “Just git on in there Boy!”

“No Daddy no. Please don’t make me do it Daddy!” After a long silence punctuated only by thunder the Judge said, “Just git on in there Boy!”

I’ve been quoting the Judge ever since. Whenever there is a horrible, hopeless, life threatening task ahead, such as the prospect of mating with an obese woman met at a honkeytonk, I say, “Just git on in there Boy!” To my great amusement my friends have picked up the phrase and still use it!

With eyes as big as saucers the boy sank into the dark waters of the swamp and clutched the log. It rather resembled the struggles of a pig being eaten by an anaconda. I jumped in to help, but to no avail. Our foray into the swamp was finished, and we returned snakeless.

……………………………………………………………………

How not to catch a snake

Over the next several years we returned often, and many adventures were had.

I learned that the Judge wasn’t actually a judge, but rather a Justice of the Peace, which made him the biggest frog in the little pond of South Mills. In addition to the restaurant, he made a good business out of the fact that in nearby Virginia there was a law requiring a prospective couple to be tested for syphilis prior to marriage. No such law existed in North Carolina. Testing took time, which could be a problem if a distraught daddy was chasing the groom with a shotgun. After crossing the border the first town you come to is South Mills where the “Judge” was a JP who could get the job done on the spot.

I so wanted to show my readers a copy of Judge Hurdle’s business card. I have it somewhere, but it is lost in my files along with my signed letter from Donald Trump telling me that he didn’t need my services as a waterfall builder because for Trump Tower, then in planning. He had hired, “The world’s best Italian stone masons, the greatest, who made drawings of each and every stone to make it look more natural.” Only Donald Trump would think that making a drawing of a stone, and paying extra for it, makes it more real.

Hurdle’s business card showed a drawing of food items and wedding rings, along with the statement, “We’ll show you the ropes and tie the knot. Double ring ceremony. Burgers and fries.”

Hurdle’s business card showed a drawing of food items and wedding rings, along with the statement, “We’ll show you the ropes and tie the knot. Double ring ceremony. Burgers and fries.”

There were moccasins galore, and many other species of snakes, especially in the late summer when the swamp had dried leaving puddles beneath the bridges. We caught them wholesale, and had many close calls.

Bubbas throughout the south are eager to attest that moccasins are vicious creatures that will attack if given the chance. There are countless stories of fishermen being “chased”, but that is all nonsense. Moccasins are more than willing to defend themselves, but will never advance to attack. They thrash around in a scary manner, and sometimes throw themselves diagonally away from the threat, but that is all. It is all a matter of misinterpretation. Here is the proof.

One day I spied a moccasin coiled on a cut off cypress stump. I waded through the thigh deep slime, and attempted to pin its head down with my snake hook, but the stump was too fissured for that to be possible.

(A snake hook is simply a stick or dowl with an “ell” shaped metal attachment on the end. They are handy for tearing apart stumps, rolling over logs, lifting snakes off the ground, and pinning their heads. I made them in shop class in high school after tricking my English teacher into believing that they were “ophidian hooks” used by the ancient Greeks during the battle for Troy.)

The moccasin slithered off the stump and into the water, so I tried to hook it up and throw it ashore, but I missed. The poor confused snake saw a towering object that looked like a cypress tree with a crack at the bottom. That crack was my crotch. It turned and suddenly swam between my legs. That was when I replaced my tonsils with my testicles, but it was just a scare. The snake swam on through. If the snake had been trying to harm me I would be singing soprano to this day.

Another time I found a huge old male. I was able to successfully pin it, but as I lifted it off the ground its muscular body coiled around my arm. Not good! That meant I couldn’t let go. Old fat snakes, like old fat people, often have loose flabby skin. I gripped its head in horror as it pulled itself backwards, the loose skin slipping over the head so that my fingers were just beyond the reach of its inch long fangs dripping with venom. I yelled for help and my friend managed to get it unwrapped from my arm. At the last possible moment I threw it free. It had been a close call.

………………………………………………………………

Small scale genocide

We caught everything we saw. Not just moccasins, but rather every snake, turtle, frog, or lizard we could lay our hands on. It was unconscionable, but then young men often have poorly developed consciences. We justified it by saying it was a “business”, a business that invariably lost money.

For me the breaking point came on a trip to the Mattamuskeet peninsula south of the Dismal Swamp. I went there to look for the fierce little red pigmy rattlesnakes endemic to the area. I failed, but caught many others later.

That trip was different, because instead of the ‘usual suspects’ I had with me my future ex wife and a Hippie who had never before left the city. We camped at an old abandoned farm where there were no fences, and the animals had long been feral. We spread out our sleeping bags in a pasture and went to sleep.

During the night I awoke to discover that the cows had returned. I could hear their footsteps going crunch crunch crunch. Have you ever heard a cow bellow? Probably, but the Hippie hadn’t. The cow let forth with a bellow that could have been heard a mile away, thus awakening the Hippie who heard the crunching coming closer in the dark. I will never forget the look on his face as I turned on a flashlight. I doubt that he has ever been the same since.

Lema, who years later was to become my wife, was beautiful, fierce, and brave with a mane of golden hair. I loved her to death. She resembled what she was, the reincarnation of a Viking warrior goddess. Here is a photo of her taken a few years later.

The abandoned farm had more than cows. There were large herds of wild pigs. While I was off catching snakes Lema took off all of her clothes and snuck up on a large herd slumbering at midday. She squatted down next to the boss boar, the big one with the giant tusks, the one that defends all the others. It woke up to discover she was inches away. Instead of ripping her apart, it slowly stood up, snorted, then walked away with a dignified gait. Anyone else would have been turned into pig shit. This encouraged Lema, so the next day I watched in horror as she snuck up on an enormous bull and tried to jump up on its back. Instead of trampling and goring her, it too ran off! As they said in ancient Rome, “Fortune favors the bold”!

Meanwhile, I discovered that the wet ditches were filled with lovely little spotted turtles Clemmys guttata, all involved in a mating orgy, a behavior that had not previously been documented.

Scooping them up by the score was easier than shooting fish in a barrel, so I caught at least fifty of them. At the time Lema and I were living with other Hippies in a commune in a ghetto in Washington DC. I was working part time (sort of) in a pet shop called The Friendly Beasties. The pet shop only wanted a few, but that left the rest which I put in the only bathtub in the commune where they continued to try to mate. Our roommates weren’t happy about that because even a dirty Hippie needs a bath once in a while, so I sold them to neighborhood black kids for $0.25 apiece, knowing full well that they would be horribly maltreated prior to starving to death.

I knew it was wrong, but I justified it to myself by saying that they were numberless. Now that they are threatened with extinction throughout their range it truly tears me apart to think of it. The awakening of my ecological consciousness came slowly. That thoughtless act was what first brought me to the realization that collecting wild animals for profit can never be justified.

…………………………………………………………

The old man who talked to snakes

One day I discovered an ancient black man living in a shack by the edge of the swamp. He had collected an enormous amount of firewood which he stored in a pile on the ground covered in black plastic. There were many such layers of wood and black plastic. It was the best snake habitat I had ever seen! A million snakes could have hibernated there.

I asked the old man if he had seen any. He replied that there were hundreds of “red belly moccasins”. These were actually harmless red bellied water snakes Nerodia erythrogaster.

I asked if I could catch some, but he refused. He said, “Naw Suh. They my friends, and I likes to talk to ’em. They comes up onto my porch ’cause I puts out milk every night.” The proof was that every morning it was gone!

Like the wonderful old wizard I described in The Old Man and the Monkey, he could talk to animals because his heart was overflowing with love for all living things, not just snakes. I consider such people to be saints who we would all do well to emulate.

Mankind has many enduring legends that span cultures and millennia, and the belief that snakes drink milk is one of them.

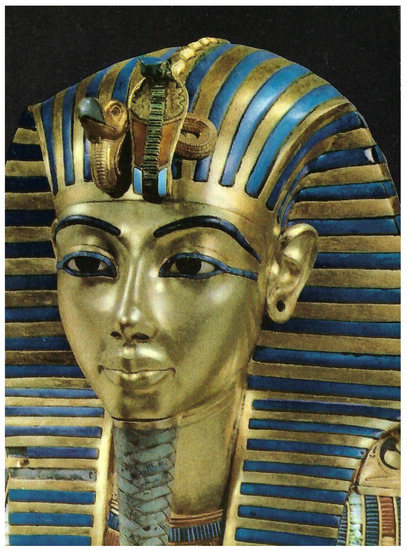

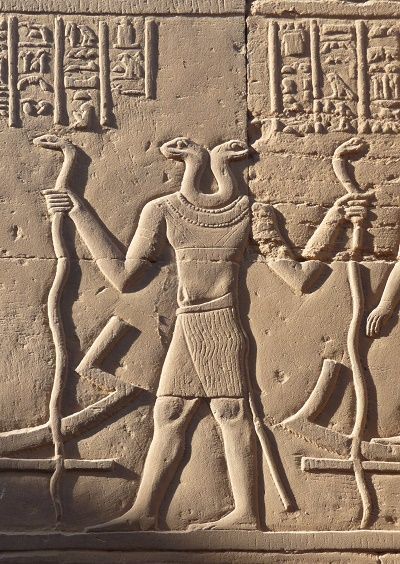

The ancient Egyptians worshipped the cobra goddess Wadjet who protected Horus, and Nehebkau, a judge of the dead. Both were propitiated with milk and flowers

There are many different snake gods in Hindu mythology, especially the great Nagas whose worship spread into Buddhism.

In various parts of Africa people worship pythons to this day. Like elsewhere they offer milk and flowers. There is evidence that in Botswana people were worshiping pythons 70,000 years ago. If so, that would be some of the earliest evidence for mankind’s practice of religious ritual.

In early Europe Slavic people once made a practice of leaving dishes of milk at their doorsteps to prevent hungry snakes from suckling their cows, or worst still their wives! “Bessie has gone dry, and now look, there’s a snake!” This belief was carried with settlers to the new world where the name milk snake (Lampropeltis triangulum) was given to a small harmless snake frequently found in barns.

The fact that snakes never drink milk is beside the point. Legends are the distillation of ancient wisdom, and their veracity is irrelevant. The old man, who was probably illiterate, was wise if not correct.

…………………………………………………………..

An astonishing discovery

One day we were driving around looking for old shacks to rummage through. There is no better place to find a snake than around a derelict building full of memories and mice rotting away in an overgrown yard. If the house has burned down and the tin is on the ground, all the better. Just look for a freestanding chimney. I got so good at spotting ruins that I could find them while driving at high speed just by the vegetation.

One day we were exploring east of the swamp when in the distance through the trees I saw something inexplicable. My first impression was of a tugboat, or perhaps a Mississippi river steamboat lost in the woods. Huh? I made a quick u turn and parked.

There were many No Trespassing! signs which we ignored, all the while being cautious about a nearby house. The site was recently overgrown. There was some evidence of other intruders, a few beer bottles, but otherwise it was just a ruin barely visible through the trees. As we approached we were confounded by what we saw.

It wasn’t a boat, and it wasn’t a house. It was an oval concrete structure at least fifty feet long that was adorned with countless inscriptions and decorative objects such as glass eyes, colored glass shards, marbles, pipes, protuberances of all sorts, and strange stones from the far corners of the earth, all embedded into the concrete.

Above us were two more levels, also oval, which were configured much like a ship. Just imagine a tugboat with a cabin above the deck, and above that a small ‘helm’ where the captain might sit. But it wasn’t a boat.

The inscriptions cast into the wall were aphorisms, some from the bible, and others from history’s greatest philosophers and thinkers. Prominent among these were the insane prophecies of Nostradamus. There were even small sealed glass ‘windows’ behind which old books had been embedded. None of these gave a view of the interior.

At the front, or ‘prow’, of the boat shaped structure was a locked door about three feet tall, like the door to a dollhouse. Next to it was an inexplicable configuration of colored pipes and notches cut into the concrete. We supposed that it was some sort of sculpture.

As we walked around the building reading the inscriptions we discovered a grotto dedicated to the Virgin Mary. There are no stones anywhere near the Dismal swamp, so the mad sculptor had fabricated them out of concrete. In the center of the grotto was a pool with a large garfish. I was amazed that such a large fish could live in such a small pool. Was someone feeding it? Like everywhere else, the grotto walls were covered with prophetic inscriptions. Scattered through the grounds were other freestanding monuments, all covered with inscriptions.

I had assumed that the ‘front’ door would be at the back of the building, but it wasn’t. There was what appeared to be a possible rear entry, but it had no doorknob, and had long since been sealed. We continued around until we got back to where we started. There was no door!

We stared in bafflement until I realized that the strange ‘sculpture’ next to the little door could be used to scale the wall. As soon as I put my hand on the protruding pipe my foot automatically found a corresponding notch. It wasn’t a sculpture, it was a ladder, the only way into the mysterious building!

We climbed ‘on deck’. The ‘cabin’ had small glass windows through which we could see something below that looked like a laboratory. Like the building itself, there was no door to the cabin. We were perplexed as to how to get inside until I noticed once again that it was possible to ascend to the ‘helm’ by climbing.

The ‘helm’ had a roof like a widow’s walk, but was otherwise open. There was so much to see that I don’t remember if there was a ship’s wheel, or not. To our astonishment, in the center of the uppermost deck we beheld an old fashioned brass fireman’s pole leading down into the interior.

We slid down the pole. It wasn’t a laboratory per se, more like an alchemist’s studio, or perhaps that of a mad apothecary.

There were retorts, scales, test tubes, and phials of all kinds. Most notable were the hundreds of tiny drawers that lined the walls. Each was carefully crafted to conform to the curving structure, and each was labeled in Latin. They contained tiny samples of dried plants, crystals, powders, and stones. There were old books, and notebooks filled with obscure entries. The entire interior was hand crafted in wood in a manner resembling that of an old sailing ship.

We were afraid we might be caught, so we climbed the pole and stole away, our minds filled with wonders.

I only entered that wondrous building one time, but later returned to the grounds several times with friends. I don’t remember who was with me, or when? In my mind the entire episode acquired a dreamlike quality. Had I really seen all that, or was it my drug addled imagination? After all, it was the late 60s.

Many years passed until I decided to return to photograph the inscriptions on the exterior. I still have those photographs somewhere, but they are hiding with Judge Hurdle’s business card, and Donald Trump’s letter. They may never be found. By that time the grounds and building had been badly disfigured by vandals, and the No Trespassing signs were larger than ever.

When the age of the internet dawned I began to make enquiries. I struck paydirt when I contacted the Camden County NC Historical Society. An elderly lady of the sort that keeps the South alive knew exactly what I was talking about. She had even published a book about the history of Camden County which included a photo, and the name of the eccentric who had created it.

I took one look at the photo and realized that it was of a different building, probably the one next door that I had so carefully avoided. The confusion has carried on until today. In both photographs and written records the wondrous building I discovered has been conflated with the home of the owner which was apparently equally odd. Because of this confusion it has been variously called the Dream house, the Bottle house, the Junk house, the Glass house, Old Spooky, and Shangri-la. All of the extant photos are of the owner’s home, not his creation.

I dug further into the county records and discovered that the ruin(s) had been considered for preservation, but had been recently torn down by the owners due to constant vandalism and partying. Blink one time and history vanishes. I was too late.

What we do know is that James Franklin Butts was born in the swamp in 1889. He was a mason by trade who slowly built his home, and his masterpiece, from whatever materials he could find. Here is a description of his home, which is not the building I discovered:

OLD SPOOKY OR SHANGRI-LA, THE HOUSE THAT FRANK BUILT

by: Dorothy G. Owens

James Franklin Butts was born in Pasquotank County, North Carolina on February 28, 1889. He married Rena Olds. They settled on a piece of land on the corner of Old Swamp Road and Bass’es Lane in the Pierceville area of Camden County, near her people. Frank built a house for his family but saved the corner lot for his dream house.

For over 40 years, Frank, a brick mason by trade, built and added onto his three or four storied house of dreams. Using steel, rocks, bricks, concrete, glass, wood and whatever material that caught his fancy. His building plans came from dreams and visions that he would have. Each room held a cryptic message of Biblical, Historical, or current events. Frank loved to show off his house of dreams, especially if they realized that each item in his house had a special meaning and a special spot. If a visitor seemed critical, Frank would become cool and aloof. He was known throughout the counties as the man who lived in that old spooky house.

Old Spooky had many rooms. One room had a staircase that lead to and ended at the ceiling. There were rooms that had doors that opened to blank walls. Doors that were placed in the ceiling and in the floor. Halls that led nowhere.

A nephew once asked his uncle Frank,” Why were books embedded in the concrete wall and covered by panes of glass”? Frank replied,” It represents all the lost knowledge in the world”. “Books that mankind had destroyed throughout the ages.”

“Many of the walls were papered with magazine articles, stories and pictures”, said a nephew. “You always had something to read and look at .” In one room a fireplace had been built with a reservoir of water above it. It represented “Hell and High Water”.

The multi-storied house had a garden on the roof. Pictures of Presidents, Biblical scenes and maps were embedded in concrete and protected by panes of glass decorated the facade. The yard surrounding the house was landscaped with seashells, homemade statues, arches and monuments that he himself had designed and made. One of his last monuments dated Nov. 6, 1962, for the Cuban blockade was inscribed “BENEATH LIES IN PEACEFUL SLUMBER – A SNAKE – A POSSUM “.

Over the years his neighbors and some of his relatives questioned his mental stability. Some even succeeded in having him committed to an institution for a short time. His church expelled him for his analogies of Biblical passages predicting battles in World War II.

Was he a genius some would ask, was he crazy or a fool? Whatever he was, Frank Butts left a legacy of wonder, mystery, and imagination to the generations that knew him and visited his Dream House. To future generations who have heard about him and Old Spooky, he has passed, like Johnny Appleseed into local folklore.

James Frank Butts died September 30,1973. His house of Dreams, Old Spooky, abandoned, began to fall in decay. No Trespassing signs were posted on the property, but curious passerbyers and local children managed to sneak in for the adventure to wonder and marvel at Old Spooky and it’s builder.

Condemned as a safety hazard, Frank Butts Dream House was demolished and carted away in late December, 2000.

This is what Howard W. Olds Sr. had to say:

Twas so sad to see them tear Old Spooky down

It groaned as it fell slowly to the ground

So many years it stood there all alone

It just wasted away after everyone was gone …

…It represented culture, it represented time

It was the culmination of man’s ability and inquiring mind

Its walls have crumbled, its floors fallen in

Like those who once lived here, it’s gone with the wind

Sic transit gloria.

If you just can’t get enough, here is another story about how a cannonball from the War of Northern Aggression wound up in the dream house.

……………………………………………………………

The Book of Mormon is better than the bible!

During the course of our many adventures I gradually began to learn more about Judge Hurdle. I still didn’t suspect that he was the local head of the KKK. To me, he was just the quintessential Redneck who, for some peculiar reason, was willing to tolerate Hippies. The Judge frequently used the word “Nigger”, as did everyone else, but I never knew him to express any personal animosity against black people. They were in their world, and he was in his. So it was that I thought nothing of tearing down Klan posters whenever I found them in general stores, and in various other locations. By the time the proprietors, who were all Klansmen, figured out what I was doing I was out the door and down the road. If I had kept those posters they would be valuable today, but I just tore them up as any good liberal from the big city would.

I must relate a ludicrous incident concerning the Judge. One day in early November I stopped at his restaurant for dinner. The weather was cold, wet, and nasty. I hadn’t seen a snake all day.

The Judge asked, “The weather’s terrible Boy, where you gonna sleep? “Well Sir, I don’t really have a plan. I guess I’ll sleep under a bridge” (Remember, this was before I learned how to camp.) The Judge was appalled. He said, “Son, I’ve got a big brick house up on the hill (there are no hills anywhere near the swamp), and you would be welcome to spend the night”. Given the alternative, I was happy to accept his kind offer.

In the morning he fixed breakfast, then said, “Son, I’ve done showed you my hospitality and given you breakfast. It seems only right and fitting that you might be willing to listen to a few words about my personal philosophy”. I readily agreed.

“Son, I’m a scientifical man. I’ve read all about that science stuff. Did you know that light had ’em a speed to it?” I asserted that I had read about the speed of light, but had no personal experience of it.

“As you may know, around here we’re all Baptists. Now Baptists are good people, ain’t nothing wrong with ’em, good bible believing folk, but now I’ve learned that there is another book even better than the bible, even truer to God’s word. It’s called the Book of Mormon”. With that he whipped out an unexpurgated copy, a page of which he had bookmarked.

“It says right here that there is a crystal planet revolving around the earth. We can’t see it because it’s crystal, you can see right through it, but we know it’s up there because it’s here in the book.” He showed me the passage.

(Note to readers: This crystal planet should not be confused with the individual planets that are granted by God to the highest levels of the Mormon clergy, especially the ones with the most wives.)

“Now why did God put that crystal planet up there? That’s when I got to thinking about all that science stuff and the speed of light. It so happens that everything you do while you are alive is being beamed up into outer space at the speed of light, so when you die God flies up into outer space faster than the speed of light, then uses that crystal planet to focus in on your life. If you’ve been good you get to go to heaven, but if you’ve been bad, Boy you are shit out of luck!”

“…God flies up into outer space faster than the speed of light, then uses that crystal planet to focus in on your life. If you’ve been good you get to go to heaven, but if you’ve been bad, Boy you are shit out of luck!”

It was a revelation! I subsequently discussed this with various Mormons, mostly of the thin black tie bicycle riding variety, and all said that the crystal planet was false theology that had been misinterpreted and expunged from the Book. Be that as it may, I read it!

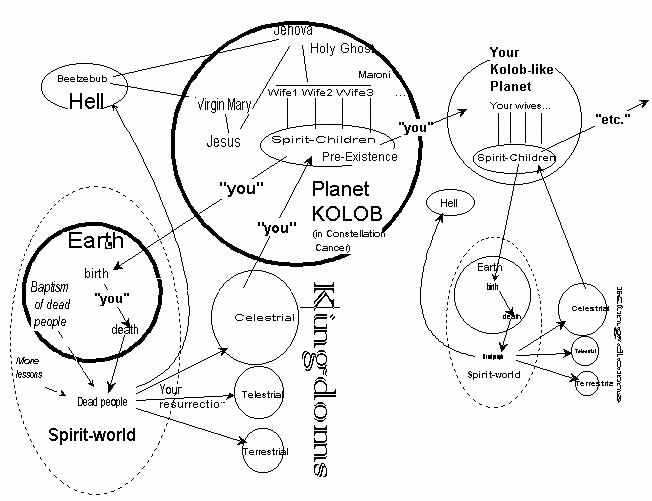

The confusion may stem from the Mormon belief in Kolob which is the star nearest to where God lives. The Mormons claim there have been no revisions, but that is nonsense! The Mormons have tried to go mainstream, so now they deny personal planets, the revelations of the great white salamander, and even plural marriage.

None of it makes any sense whatsoever, which may explain the metastatic spread of Mormonism throughout the Klanosphere.

……………………………………………………………..

We blow up a Klansman’s house

One day Louie, Wayne, and I headed south in Louie’s Volkswagen beetle. Along the way we picked up a large number of M-80s and cherry bombs at a roadside fireworks stand. Those were the days before there were regulations against children having high explosives. Some M-80s were equivalent to a quarter stick of dynamite. Any of them could blow you hand off. They were lots of fun!

In South Mills we stopped by Hurdle’s restaurant. He suggested that we take his retarded son along for the ride.

Somewhere deep in the swamp we found an old house. It was in good shape, but apparently abandoned. We searched for snakes but didn’t find any. What the heck, let’s see what an M-80 will do to that old icebox. Kaboom! Hey, here’s a knothole in the wall, lets drop one down there. Kaboom! Here, catch! Kaboom! It must have sounded like the outbreak of the next world war. None of us were injured, but the damage to the house was extensive.

We had failed to notice that just beyond the trees there was another house where the owner lived. Suddenly, an old man who looked like Snuffy Smith came charging toward us in an ancient pickup truck with his shotgun waving out the window. It was just like a cartoon. We leapt into the VW and sped off at our top speed of 35mph with the old man in hot pursuit. It was nip and tuck as we slalomed around the swamp, but we eventually lost him.

We were certain that he would call the cops (presuming he could find a phone), so, being Yankees with Maryland plates, we decided to go south to throw them off our tracks. There was only one hotel in Elizabeth City. We had just checked in when the call came through. “it’s for you, Boys.” The Judge had somehow found us.

He said, “The old man recognized my retarded son, and there is no way in Hell the cops won’t catch the only VW full of Hippies in eastern North Carolina, so I told them y’all had gone back to Maryland. Now looka here, I’ve got a little problem, and y’all are gonna help me solve it. That man whose house you blew up is an enemy of mine because he heads up a rival faction of the Klan. That ain’t right, the Klan needs to be unified, and we need to be reconciled, so here’s what y’all are gonna do. Y’all are gonna get your asses back to the restaurant and you’re gonna apologize to him real nice like. Him and me, we’ll be friends again after that.”

We drove back to South Mills with our tails between our legs and apologized. The old man was a reasonable person. He said, ” Y’alls was just being boys, but I wish you hadn’t blown up that icebox. It belonged to my grandmaw.” I was truly abashed. The icebox had been a hand painted artifact of a time gone by, and a precious memory. We had been the worst sorts of thoughtless vandals, and deserved far more than we got.

How could it be that both Judge Hurdle and this nice forgiving old man were both leaders of the Klan? They were both good people! I never heard either of them say anything bad about black people, or anyone else. They were even tolerant of Hippies from Maryland!

I had been taught since childhood, and since then by the media, that the KKK was an evil organization filled with hateful people who terrorized innocent blacks, and whoever else they disagreed with. Every image reinforced the stereotype. Have you ever seen an image of the Klan that didn’t feature a burning cross surrounded by men in sheets?

I had seen a different side. Unlike all of my liberal friends who profess to despise the Klan from the safety of their distance, I had actually fought them on their own ground. I had ripped down their posters, and even blown up a Klansman’s house!

The Klan has done many bad things, but for most of the members it was just a culturally conservative fraternal organization dedicated to the maintenance of the status quo, not much different from the Elk’s club or the Odd fellows. It is true that they wanted to keep the blacks “in their place”, but in retrospect, given the sorry outcome of integration in our cities, perhaps that view was not unwarranted.

As for the fierceness of the Klan, it was all bluff. A decade before my time in the swamp the Klan decided that the Lumbee Indians were in cahoots with the blacks, both of whom presumably wanted to ravish white women. They organized a typical rally in Maxton near the South Carolina border. At that time Robeson county was inhabited by approximately equal numbers of whites, blacks, and Indians, a perfect recipe for a problem. Things were going along as usual with a flaming cross and bombastic speeches, when suddenly the Klan realized they were not alone. Just out of the circle of firelight several hundred Lumbees had assembled with guns. When the fun began it was an all out rout. The Klansmen fled into the night, totally humiliated. The Indians dressed up in the discarded paraphernalia and had a fine time! It was called the Battle of Hayes Pond.

The Klan never recovered from the defeat. Thereafter, they were regarded as a joke by everyone except urban liberals who forever yearn to keep hatred alive so that they can have something to stand righteously against (at a safe distance).

…………………………………………………………..

We were growing up. Times were rough back at home. My grandmother was dying in a nursing home, and my mother was distraught, not just about the impending death, but also about the worthlessness of her son who was flunking out of junior college yet again, and had no job prospects. It seemed the ordeal would never end. My mother said, “Go ahead and take a trip, there is no way to know when this will end. Have fun, and be safe.”

Pete and I were hunting snakes in the Mattamuskeet peninsula, and had found plenty. We stopped at a general store in the tiny town of Fairfield to get a cold drink. As soon as we did, the blacks who had been lounging in the shade rushed up to say, “Yo grandmama done died, you gots to call yo mama!” How was that possible? No one knew us in Fairfield???

I found a payphone and called Mom. It was true. Grandmother had died several days before, and Mom was desperate to contact me so I could attend the funeral in Charlotte. She didn’t know what to do, but she had some idea of where we were, so she asked the telephone switchboard in Plymouth NC who she should talk to. (Remember when you could still ask for information from a real live operator?) The nice lady said, “Don’t you worry ma’am, Sheriff Bubba can find him!” (I don’t remember the Sheriff’s name, but he was locally famous, a Bull Connors kind of guy, and no doubt a Klansman.) The Sheriff knew we would eventually stop for a soda pop, so he alerted all the black people in all the little towns to be on the lookout.

Time was short, so Mom had already made arrangements with the Coast Guard in Elizabeth City to fly me to Charlotte. Pete drove me to the Coast Guard Station. When we arrived we were confronted on the tarmac by a group of Guardsmen who sneered and jeered at the long haired Hippies. “Get a job! Take a bath!”

While we were standing there, one of the younger Guardsmen walked over to ask if he could stand with us in solidarity. He wished that he was a Hippie too. Sure, why not? He asked why we were in the ass end of North Carolina, so we told him we had been snake hunting. “Did you catch any?” We had a big bagful!

He said, “I sure wish I had a big bagful of snakes”. Why, I asked? “If I had a big bagful of snakes I would let them all loose in the officer’s mess. Then they would surely throw me out of the Coast Guard!” That seemed like a good plan, and we didn’t need them. None were venomous, but all were ugly, mean, and looked like moccasins. I handed him the bag and wished him the best.

……………………………………………………………..

By that time I had turned twenty one. The Great Dismal Swamp had been a grand adventure, but it was time for me to see the world.