Prelude:

This post is a bit of an anachronism. All of the other adventures chronicled in this series about Kanchanaburi province in western Thailand took place in 2016; however, that was not my first trip to the magical realm.

During the winter of 2008-2009 the Wandering Weazel undertook an ambitious two month long southeast Asian adventure, first to southern Laos, and then to various National Parks throughout Thailand. Brief side trips were also taken to Cambodia and Myanmar.

Toward the end of that journey I visited Tak province in western Thailand, then continued south to Umphang district which is arguably the most remote place in Thailand. There I visited the magnificent Thi Lor Su waterfall which is one of the wonders of the world. I will chronicle those adventures in a future post.

From a cultural perspective Umphang is really a piece of Burma (Myanmar) that just happens to be in Thailand. It is cut off from Tak province and the rest of the world by wild jungles and the complex folding of the Tenasserim range. There is only one road in or out, and it is known as the “Highway of Death”. (I should mention here that what I am calling jungle is actually seasonally dry monsoonal forest rather than rain forest.)

None of this has stopped many thousands of Karen refugees from pouring across the frontier to escape governmental persecution in Myanmar. Huge refugee camps spread across the denuded mountainsides. The Karen people have nothing, only dirt to eat and teak leaves for their roofs, yet their dignity in the face of travail has to be seen to be believed. They acknowledge that they are guests in Thailand so they conform to social norms and speak only of their desire to return to their homeland. If and when they get a cup of rice they are eternally thankful. For these and other reasons the Karen people quickly earned my respect.

I was equally impressed by the Karen homeland, the wild and beautiful mountains that separate Myanmar from Thailand, so I resolved to continue my explorations.

There was still time for one more side trip so I decided to visit Chaloem Rattanakosin National Park in Kanchanaburi province. It is located a relatively short distance south of Umphang as the crow flies but is very difficult to get to. I chose Chaloem Rattanakosin because the guidebook said it was rarely visited due to its remote location, and there was nothing to do other than to explore a cave known as Tham Than Lot. All of which sounded perfect to me!

There was no direct way to get there because the border between the two provinces is protected by the Thungyai Naresuan and Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuaries. These are two of the world’s most important protected areas. Both sanctuaries are generally closed to tourism, and are home to some of the last viable populations of wild elephants and tigers.

As you can see most of southern Tak province, Umphang, and northwestern Kanchanaburi province is protected in one way or another. Logging, hunting, and the building of new farms is strictly prohibited, though a certain amount of latitude is given to the inhabitants of remote rural villages.

Thai conservationists are practical people. A ranger might turn a blind eye to a hungry man who cuts firewood or snares the King’s rabbit, but shoot a tiger and he will shoot you. Don’t bother going to court, the judge will ask, “Did he or didn’t he have a gun?” We need to take the same approach whenever right wing fanatics take over our public lands here in the United States.

Most importantly, the Thais protect land through the simple expedient of not building roads. That means there is no way to get from Tak province to Kanchanaburi province other than by walking. Anyone who does risks being flattened by an elephant or being turned into a tiger turd, so I decided to take a bus.

Sleeper buses go directly from the city of Tak overnight to Bangkok. These are deluxe rigs with fully reclinable seats, picture windows, and bar service. “Would you like a hot washcloth with your cold beer Sir?”

From Bangkok it would have been easy to catch another bus to Kanchanaburi then somehow on to Chaloem Rattanakosin National Park. The problem was that I didn’t want to go to Bangkok so I decided to get there the hard way by taking local transportation.

Lost in the countryside:

My first stop was Uthai Thani, a nondescript town with little of interest to a tourist. No tourists meant no English was spoken which complicated things considerably. I had no idea how to pronounce Chaloem Rattanakosin. Even if I could pronounce the words no one would have known it by its official name. I pointed to it on the map but that didn’t help either because most Thais cannot read maps and know nothing about anywhere except where they live.

After much gesticulation a fellow offered the suggestion that I should travel first to the tiny town of Nong Prue; unfortunately, he had no idea how to get there so I had to inquire elsewhere. The problem was that I couldn’t pronounce that place name either. These look like simple words when transliterated into English but the Thai pronunciation of Nong Prue sounded something like the noises a cat might make whose fur was being rubbed the wrong way.

Thus began a multi day Odyssey by chicken bus, songthaew (a pickup truck with bench seats in the back), and tuk tuk (a motorized tricycle) that eventually deposited me on the outskirts of Nong Prue. There was nothing there but an abandoned bus stop by the side of an empty road, so there I sat wondering what to do.

Eventually some Buddhist monks in saffron robes showed up. They were already halfway to Nirvana so they nodded and smiled regardless of what I said or did. Later, some rather more worldly old ladies arrived at the bus stop. They were intensely curious as to why a Farang would be in such a place. Where, pray tell, was I going? And why?

I tried and tried to pronounce Chaloem Rattanakosin but to no avail. No one had ever heard of such a place. Eventually I heard one of the old ladies mumble something about Tham Than Lot. That rang a bell so I looked in my guidebook to discover that was the name of the cave! (Tham means cave in Thai). I should also mention that transliteration between Thai and English is an imperfect art so spellings may vary. For example, the name of the cave is also spelled Tam Tan Lod.

By this time a small crowd had gathered and they all smiled and nodded in approbation. “Yes, you go Tham Than Lot, very good!” I gathered that any Farang who went to such a place couldn’t be all bad.

The riddle was solved, but I still had to get there. An old man explained things to the bus driver but he shook his head, it wasn’t on his route. That was when the old ladies sprang into action and besieged the poor driver until he agreed to take me where I was going. No one ever dares to argue with a gaggle of hags in rural Thailand!

Almost every rural village in Thailand is accessible by some form of public transportation. If the bus doesn’t go there then a songthaew will, even if it only goes once a week. The problem was that the Park was not a village, few people live in the area, and individual travelers rarely visit so transportation was non existent.

Please understand that this was a full sized bus full of paying passengers that followed a designated route on a paved road just like here in the good old U S of A. Now imagine an American bus driver deviating from his route to take a single passenger more than fifteen miles out of the way on a very bad single lane dirt road through the mountains. If he wasn’t beaten to death by the outraged passengers then he would certainly be fired when he got back.

But this was Thailand where kindness and generosity are the norm, so the other passengers, who presumably had better things to do, actually cheered the driver on as he bravely bounced his way up the tiny road. When we arrived at the Park gate it was impossible for him to turn around so he had to back down the mountain while the passengers all waved goodbye.

Received like a long lost son:

At the gate I was greeted with beaming smiles by a cute young woman holding a new born baby. She observed that my pack was much too heavy so she urged me to put it down. Just to be sure she tried to move it a few inches but couldn’t. That generated more smiles and a quick squeeze of my biceps. “You velly strong man, good! But campground too far. I get ride for you!”

With that she thrust the infant into my arms and ran off to make a call. (Excellent phone and internet service is available everywhere in Thailand.)

What sane mother would entrust her child to a stinky foreign stranger who obviously hadn’t bathed or shaved in a very long time? I was terror stricken by the wriggling maggot, but a nearby farm girl noticed my plight, giggled, then relieved me of my burden.

In short order a fine young man, presumably a ranger, arrived on a motorcycle to take me to the Park headquarters more than a mile away. I was very reluctant to ride on a motorcycle while carrying my gigantic pack, but to him it was nothing because he was accustomed to carrying the whole family along with a pig or two.

The ranger took me to the Park headquarters and introduced me to the Superintendent, a spiffy fellow in a crisp uniform who spoke excellent English. He was effusively friendly as he welcomed me, obviously impressed that I had come alone by means of local transport. (Thais, like many oriental people, prefer to travel in organized groups. It is very unusual to meet a solitary Thai traveler.) He was even more impressed that I had all the necessary camping gear and needed nothing but his permission to be there.

The superintendent said I was free to explore the cave(s) by myself, but that I must enter and exit between 10am and 4pm. I later learned that this was because the so called Little cave, Tham Than Lot Noi (Noi means little in Thai), had lighting that was only turned on during those hours. It never occurred to him that I had lights of my own.

It was February, the burning season, and smoke filled the sky. While traveling through rural Thailand I had become increasingly dismayed by the ruined agricultural landscapes. What had once been monsoonal forest had been degraded into sere brown scrub due to fires set every year by farmers.

It was understandable that the fertile flatlands had long ago been converted to rice paddies, but the hillsides were barely arable, useful only for the collection of firewood. Now even firewood was scarce because the tropical deciduous trees characteristic of a monsoonal forest had been replaced by bamboo and other fire tolerant species which form impenetrable thickets just waiting to burst into flame. It was very depressing to see that this slow motion ecological disaster had reached deeply into the Park.

All was not lost, for some low elevation areas still featured mature forest.

So it was that I was delighted when the ranger took me to the campground where I discovered a shady grove of Dipterocarps beneath which to place my tent. I was equally delighted to discover that I was the only visitor!

Dipterocarps are enormous hardwood trees that emerge from the canopy to dominate forests throughout southeast Asia. These magnificent giants are Thailand’s treasure but they have been eliminated almost everywhere due to logging and agriculture. Their presence was proof that at least a few keystone species are being protected by the Park even if the overall ecosystem is otherwise unraveling. Despite the presence of other nearby protected areas the Park is simply too small to host resident populations of charismatic megafauna like elephants and tigers.

I was happy with my campsite, but what to do about dinner? On my way into the Park I had passed a cluster of shacks where I was told that food could be purchased. It was quite some distance away; so, after a long trek I was disappointed to discover that no one was home. Coolers full of cold beer tempted me but there was no one to pay.

A small noise alerted me to an old woman in the back hunched over a bucket full of burning charcoal. (In Thailand people often cook small amounts of food over specially designed buckets that are similar to a hibachi.) She was surprised and somewhat alarmed to see me. What on earth was a Farang doing here by himself?

I grabbed a beer then asked for food in broken Thai, but she shook her head. No food! Then I pointed to the bucket, rubbed my belly, and mimicked eating. She had food and I wanted some! Again she shook her head and said, “Phet mak!” (Too spicy!), for rural Thai people presume that Farang cannot possibly eat spicy Thai food. My vocabulary wasn’t up to an explanation so I walked into the kitchen then grabbed a plutonium grade chili pepper and swallowed it.

She was astonished when I smiled through my tears, so she gave me the thumbs up sign. Apparently I was tough enough so she brought me a plate of food.

Needless to say it was absolutely delicious! As you can see I was reading “The Reivers” by Faulkner. There is nothing like a taste of Mississippi to make Thailand seem even more exotic.

The food is bad in rural backwaters almost everywhere on earth. In Mississippi people eat grits and hog jowls. In Mexico they eat tortillas and pray to the Virgin Mary for beans. In the swamplands of Washington DC Donald Trump eats overcooked steak with ketchup. In Belize they consume a vile concoction known as “bile up” which does in fact bring up one’s bile. But in rural Thailand even the poorest of the poor eat like kings and queens!

It was so good that I ordered another bowl, only this time I asked for it to be extra spicy! My hostess was so pleased she did a little jig then whipped out her cell phone and called her various relatives to come watch the Farang eat. A small crowd arrived in moments, and all applauded me when I finished dinner.

From that moment on I was part of the family. More children were dumped in my lap, special tidbits were proffered, minor wounds were tended with loving care, and for the next several days the ranger wouldn’t let me walk anywhere. The moment I left camp he would immediately arrive on his motorcycle and offer me a ride, so I never had to walk to the restaurant again. There is no other place on earth where people are so genuinely friendly.

The little cave:

In the morning I set out to explore the so called “Little” cave which was quite near camp. No sooner had I begun to walk up the path when a young woman approached to remind me that the hours were from 10am to 4pm. Reminding visitors of the hours was her only job, but I was the only visitor, so for the rest of the day she had nothing to do.

Overstaffed you might say? Hardly! In America we close our parks rather than pay minimum wage to rural workers who would otherwise be jobless; but in Thailand where nepotism rules everyone who is related to the Boss or is his friend gets a job no matter how humble the station. Not only does everyone get a job, but everyone shares the work. That means the Superintendent helps Granny rake the yard while the ranger helps in the kitchen. Meanwhile, the kids pick up trash whenever not busy chasing lizards. Nobody gets rich but everybody gets by.

In this regard Thailand is the antithesis of America. Our society is based upon fear and greed, a war of all against all, so it is hardly surprising that our penchant for rules and regulations has led to the establishment of a totalitarian state. Thailand has rules and regulations too, but the enforcement of any rule is secondary to kindness, civility, and acceptance of personal responsibility.

Ding Dong the dimwit may only be capable of following a cow but that is his job and he is proud of it. He receives little or no wage, but he has a home and food because he works on his uncle’s farm. In America he would be homeless or in jail and taxpayers would foot the bill.

After assuring the young lady that I would be out by 4pm, I put on my headlamp and entered the cave. The headlamp was completely unnecessary due to the crude but effective lighting.

“Little” Tham Than Lot Noi was little only by Thai standards. It was a large borehole stream passage about a quarter of a mile long that in Tennessee would have been considered a big cave by anyone’s standards. There was little to see for periodic floods had limited the development of speleothems and there were no evident side passages so I hurried on through.

I emerged from the upstream entrance into a beautiful secluded valley. The hills above were scorched, brown, and covered with thorny bamboo, but the valley floor was lush and green with gallery forest along the stream.

Attack of the giggling lady boys:

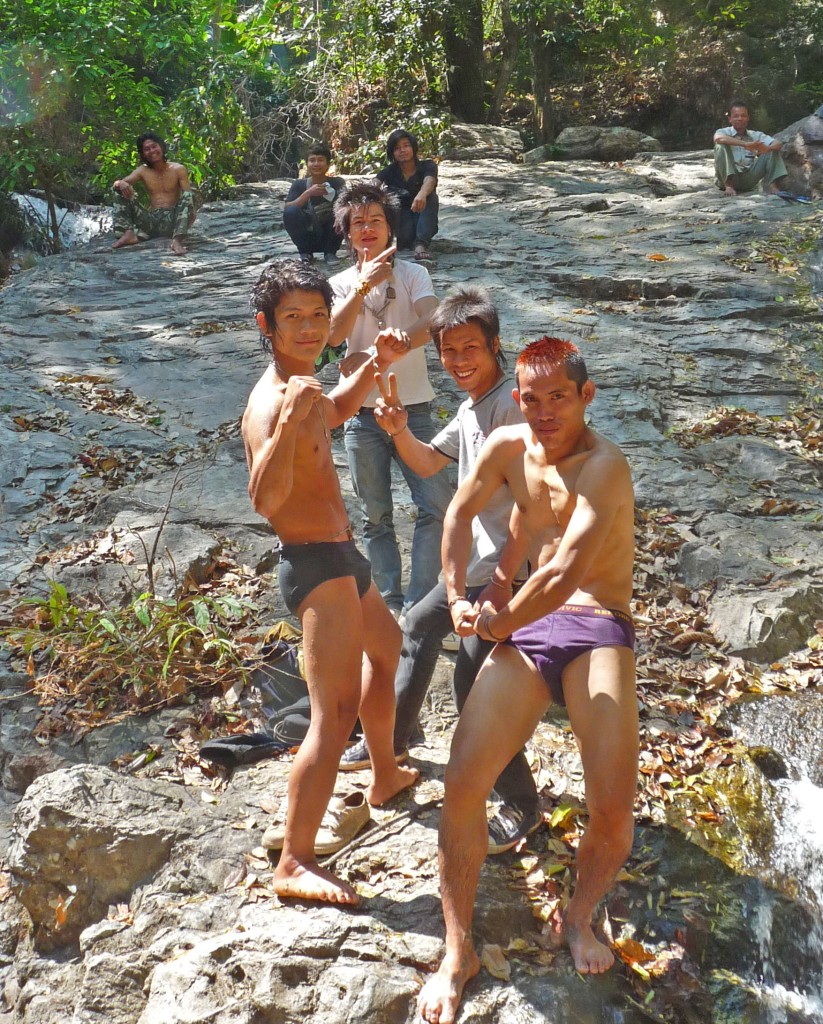

I paused to sit upon a rock and burn the sacred bud when suddenly the silence was shattered by howls and giggles as a troupe of androgynous young men pranced up the trail.

All were very effeminate and some wore lipstick so I wasn’t sure whether or not they were Kathoey boys. Whatever they were they were having tons of fun and were the loudest Thai people I have ever met. They greeted me with shouts and wild gesticulations then raced on ahead, thus destroying any hope of wildlife observation.

This was not the only time I have chanced upon groups of Thai teenagers out for a lark whose appearance and behavior had homoerotic overtones. The Thais are much more accepting of sexual ambiguity than most Westerners, so I think it is “just a phase” that many young men go through in the process of growing up.

About half a mile ahead I met them again at a small waterfall whereupon they broke into various “manly” poses.

Then we all went for a dip. It was great fun. I ain’t skeered of no Kathoey boys!

Above Nam Tok Trutreng (Nam Tok means waterfall in Thai) the path appeared to end. I was at the end of a box canyon with nowhere to go, yet I had thus far seen no indication of the so called Big cave, Tham Than Lot Yai (Yai means big). Even more curious was the fact that the waterfall was composed of metamorphic rock. Limestone was nowhere to be seen, so how could there possibly be a cave?

Through the great arch:

I noticed a very scary looking wooden ladder going straight up the cliff. No way! But I wiggled a few of the wooden rungs and they were solid as a rock; so, with great trepidation I gave it a try.

Up and up I went, carefully testing every rung. The ladder led to a series of bridges spanning the stream, then ascended a vast pile of fallen rocks surmounted by strangler figs. It was a wild and scenic landscape that would have been difficult or impossible to traverse without the well constructed ladders and bridges.

The path turned and I beheld a magnificent scene that I will never forget. Directly in front of me was a gigantic stone arch. The stream I had been following flowed through the arch and was surrounded by lush jungle. I could see right through the mountain!

Tham Than Lot Yai was indeed big. The passage was nearly 200 feet tall, but so short in length that light from the entrances enabled tall trees to grow inside the cave. There is nothing I like better than a cave that requires no lights!

The path led right through the cave. Once inside I beheld a magnificent skylight in the very center of the arch.

The skylight was at least 300 feet tall!

The great chamber was a worthy abode for the Gods, but which ones? The Buddha of course!

Thai people are almost all devout Buddhists, so why was there also a shrine to Ganesha, a Hindu deity?

At some point in the distant past this cave must have served as the frontier between two faiths. It was clear that I was entering another realm, not just of belief, but also space and time. For thousands of years the fortunes of such deities and the religions they represent have waxed and waned just as armies have come and gone. Because both Buddhism and Hinduism are relatively tolerant belief systems the people who live here today have come to accept the presence of ancient and alien Gods as part of everyday life, much as they accept the pre-Buddhist animistic entities that inhabit the spirit houses by their doorsteps.

How different this is from the current clash between Islam and all other ideologies. If this were the Khyber pass I would have found a wall of razor wire backed up by opposing armies with nuclear weapons. Instead I found a gong with which to bring good luck.

Perhaps it was rude of me, but I simply could not resist. The gong was very heavy and made of bronze, so when I whacked it with the clapper the clang inside the cave was deafening. The enormous passage no doubt served as a megaphone so I am sure that people many miles away looked up from their rice paddies to think, “How nice. There goes a Monk on a pilgrimage. May he receive a thousand blessings!”

Having thus disturbed the peace I continued on through the cave to the upstream entrance.

The hidden Burmese village:

I continued through the cave and out the other side. It was puzzling to see that the path was more heavily used here than elsewhere, for I had presumed that there would be no people living in such a remote location on the back side of a cave atop a mountain. That was when I noticed a barely discernible side path leading steeply upwards toward the top of the arch. There was a tiny sign, but I can’t read “No Trespassing” signs regardless of the language.

The climb was treacherous because the way was strewn with the dried leaves of the ever present thorny bamboo. The fallen leaves were as slick as glass, mostly because they are actually made of glass, Silica to be exact.

There are a few bamboo specialists such as the Panda, but most herbivores won’t touch either the leaves or stems because to do so would be like eating fiberglass. Even worse is the blackish fuzz that grows on the leaf sheathes of newly emergent bamboo shoots. This evil fuzz is composed of microscopic glass needles that embed in the flesh of whatever touches the culm; then, when growth is complete the tiny needles fall off to join the smoke and other airborne pollutants that make it difficult to breathe or even see during the Thai dry season. One might as well be in Los Angeles.

The trail led right to the top of the skylight, but the rock was too unstable to get a good view looking down into the cave. I did, however, get a panoramic view of the surrounding wild landscape.

At the very top I was astounded to discover that I was in some sort of weird fairyland with tiny houses designed for dwarves.

I am quite familiar with Spirit houses, but these were entirely different. Some were simple meditation platforms as seen above, but most were actual tiny houses precariously affixed to the edge of the cliff. These were much too small for a normal human, and should the vines that held them together break the meditator, dwarf, or whoever, would fall hundreds of feet to their death. I have no good photos because I was afraid to approach them. In front of these odd structures were carefully swept perfectly straight paths that looked for all the world like bowling alleys. I have no explanation for any of this.

After descending the bamboo slippery slide I continued west along the main trail across the mountain and soon came to a strange village whose inhabitants were clearly Buddhist but not necessarily Thai.

The trail led directly to a large building. It wasn’t really a temple, more like a community center complete with a library (Books are generally scarce in Thailand).

There was no one to ask, but the architecture was reminiscent of the teak post and beam buildings I had seen in Umphang, so I concluded that the inhabitants were either Mon or Karen tribespeople. In other words I had found a tiny bit of Burma hiding deep in the mountains of Kanchanaburi, Thailand.

I was eager to explore this hidden world, but I had promised my gracious hosts back at the Park that I would be out of the “Little” cave by 4pm so I had no choice but to rush back through the cave and down the mountain.

Where else in all the green and wonderful world can someone make such extraordinary discoveries in one short day, all the while enjoying the hospitality of the kindest and most generous people on earth? Only in Thailand!

Only one problem remained, how to return to “civilization”? It would be a week until the next supply run, and there were no other options, so the Park Superintendent offered to take me himself. I protested that such service was above and beyond the call of duty, but he insisted. Not only did he drive me many miles on bumpy roads to the small town of Dan Chang, but he also took me to an ice cream shop and refused any payment whatsoever.

There was some question as to whether the bus would stop at the ice cream shop, so the Superintendent summoned a street urchin and explained things. As a result, when the bus finally came to town it was commandeered by an army of kids who would not let it leave until I was safely aboard. Only in Thailand!

In the next installment of this series we will return to Kanchanaburi province in the year 2016 to explore the legendary Three Pagodas Pass, so stay tuned!

Fantastic !!! What a wonderful story and so well told.

LikeLike

Agreed. Well done, Weasel. Lovely photos. Sad to read about the burned high lands areas.

LikeLike

Absolutely beautiful photos. Enjoyed immensley

LikeLike

An enjoyable and amusing read, Weazel.

Keep the tales coming…

LikeLike

This is terrific- enjoyable and enlightening- and I am so jealous of your travels! The pictures are gorgeous.

LikeLike

Your narratives leap from strength to strength. Astounding! Many thanks!

LikeLike

Incredible topography. Great story Wez thanks!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for letting me travel along, peeking over your shoulder! I love these adventures!

LikeLike

Once again, an illustrative stroll through mud, insect bites and local fare. I was so engrossed, the mid-stride Thai gay porn skipped by until I realized what you were doing over there.

LikeLike