After our brief sojourn in the cold dry sky high city of La Paz it was time to return to the hot and sticky Jungle, so we hopped an internal flight headed northeast across the Andes to the little town of Rurrenabaque at the foot of the mountains. Needless to say, the scenery along the way was spectacular.

Now you can see why there are so few roads in Bolivia. We could have taken the famous “road of death“, but even with recent improvements the journey would have been long and arduous.

After our short flight the clouds parted to reveal the Rio Beni and the little town of Rurrenabaque.

We checked into an enormous derelict hotel perched precariously above the river.

Notice that large sections of the roof are missing. That’s not the bad part. The entire building was constructed of unreinforced brick and river cobbles mortared together only one stone thick. The slightest tremor would have turned the place into a pile of rubble, but by some miracle it hadn’t happened yet. Nevertheless, it had it’s charm. We were astonished to discover that the place was full of young Israeli solders.

We were astonished to discover that the place was full of young Israeli solders.

“Rurre”, as it is called, is famous among “mochileros” (backpackers) as the gateway to the jungle. There are a few other small towns at the foot of the mountains that give access to the jungle, but this particular speck of nowhere became an ecotourism destination because of the catastrophic mishaps of a young Israeli named “Yossi” Ghinsberg who, after being released from mandatory military service in 1981, decided to see the world. Since he was from Israel, I have to wonder if he had ever seen a tree that wasn’t part of an irrigated orchard. He certainly had no clear concept of how to deal with the jungle.

I’ve read his book “Jungle: A Harrowing True Story of Survival” the autobiography that made both him and Rurre famous. It is a poorly written tale of one bad judgement after another, starting with the decision to follow a charismatic con man on the lam deep into the jungle to search for gold. What could possibly go wrong?

There were the usual encounters with snakes, jaguars, Indians, raging floods, rotting feet, endless rain, starvation, and despair. A mutiny led to the deaths of two of the four fools involved. After the others disappeared, Yossi and his American friend Kevin plunged over a waterfall whereupon they soon became separated. After three weeks of starvation in the wilderness, long after everyone else had given up hope, Yossi was miraculously rescued by Kevin and an Indian guide.

His ordeal became a sensation, and his book a best seller. It even led to a B grade Hollywood movie. Ever since, Rurre has been a mecca for young Israelis in search of adventure, which explained the large group of idiots in the basement disco of my crumbling hotel.

It was immediately apparent to me that these people were very different from the American Ashkenazi Jews with whom I was familiar. For one thing, they looked different. They were swarthy and unattractive, socially awkward, and were behaving stupidly in small but important ways. I gathered that they were predominantly Sephardic Jews, Mizrahi Jews, or some mixture thereof. Most were speaking English, so I kibitzed with them. It appeared that, on the whole, they were less intelligent than my Jewish friends back home, all of whose children are above average. (That’s a joke you dummy!)

Though group differences in IQ are a highly controversial subject among doctrinaire leftists who support the fallacy that all racial and ethnic groups are of equal intelligence, it well known among Jews themselves that Sephardic and Mizrahi (Arabic) Jews are on average less intelligent than the Ashkenazim.

What could account for such a phenomenon? The answer to this conundrum, like so many other intractable problems, can be found in an understanding of evolution.

There is genetic evidence that ancestral Jewish groups experienced several “bottlenecks” in which population numbers plummeted, thus concentrating otherwise rare alleles. The Diaspora further isolated those who headed north to live in urban centers. Due to religious persecution and a failure to assimilate, these wandering Jews were subjected to intense natural selection for high intelligence. Get smart or die! Meanwhile, back in the desert, their coreligionists lived like Palestinians and continued to herd goats, a task requiring little thought. The Israeli soldiers that I met in Rurrenabaque were the descendants of those Jews who had not left the Levant a thousand years ago to make a new life in Europe.

They were just dumb kids living in La La land, glad to be anywhere other than where they were from.

All of this happened two years ago, before the October 7, 2023 massacre by Palestinian terrorists. Were I to meet them today I believe would find serious young men and women battle hardened against an implacable foe that must be defeated at any cost.

……………………………………………………………

One might reasonably ask what any of this had to do with my desire to get lost in the jungle. The answer is that Yossi’s travails brought international attention to an otherwise obscure part of the world which is now part of Bolivia’s Madidi National Park.

In the image above notice that La Paz and frigid Lake Titicaca can be seen at bottom left. Rurrenabaque is in the upper right corner. Northwest of Rurre is Madidi National Park, and south of Rurre is the Pilon Lajas Biosphere reserve.

Whenever a new patch of jungle inhabited by innocent Indians comes to light leftist do-gooders rush in to advise the inhabitants that they are oppressed. The presumption is that the “natives” are indigenous (which is not true in this case), and that as indigenous people they are by default “guardians of the rainforest”, and possess “sacred” knowledge. They are oppressed by virtue of the fact that they never sip lattes, drive electric vehicles, or participate in international conferences to address “injustice”.

The standard solution is to advise these unfortunates to organize “collectives” intended to control all foreign visitors and screw them out of every possible penny. In other words, they are given a blueprint for membership in what I prefer to call an eco-tourism cartel.

Here is the logic. If someone in New York City has to pay a taxi driver $50 to go a few blocks to a shitty hotel that costs $300 per night would it not be fair for an Indian to charge the same amount for a short dugout canoe ride to a thatched hut that also charges $300 per night? For an additional $100 per person per three hour excursion (group rate!) an official Indian guide will point out items of interest. “Look Ke-mo sah-bee that is what we call a tree, and on the tree sits a sacred hookey dookey bird. Are there trees where you come from?” (If the visitor is an Israeli or an urbanite the answer would be no.)

This, despite the fact that the same Indian would otherwise make either nothing whatsoever, or at best $3 for a day of hard labor.

I have no problem with anyone who wants to get ahead by charging a plump chump a premium for some service, and I also understand that conservation needs to pay for itself, but for a retired naturalist living on social security the cost of visiting an eco-lodge is prohibitive.

A presumption which underlies any eco-tourism collective is that the entire community will profit from the exorbitant fees paid by visitors. Unfortunately, as George Orwell informed us in Animal Farm, “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others”. In reality, those who run the collective prosper while others do without. The economic disparity thus created tears apart the social fabric of otherwise egalitarian communities. In the good old days you could visit Grandma upriver for the cost of a bunch of bananas, but now the canoe has comfortable seats filled with tourists, so Granny will have to wait.

The worst part of all this is the artificiality of the experience. One has no option other than to sign up for a tour. Independent exploration is forbidden, visitors are accompanied by a guide at all times, and the emphasis is frequently on antiquated tribal customs passed off as current culture rather than on a direct experience of nature.

A tour is by definition antithetical to a real adventure. You can have one or the other, but not both. Yossi had a real adventure; whereas, a tourist only takes a tour. I’ll be damned if I will travel thousands of miles and spend a small fortune to learn how to make a clay pot, watch a dressed up Indian dance, or paddle a canoe for ten minutes to catch a glimpse of a hookey dookey bird!

So, for me, the downside of the celebrity that Yossi the Wandering Jew brought to Rurrenabaque was the creation of the Chalalán eco-lodge, a state of the art facility that set the standard for eco-tourism in the region. It is undoubtedly a beautiful place, and the monies thus accrued have insured the protection of area wildlife, but the cost for a single person to visit the lodge for a few nights is approximately $1500. Needless to say I haven’t been there.

From the perspective of the Indians, whenever a presumably rich white man shows up either they get paid or something bad happens, so I can hardly blame them for being suspicious of someone such as myself who simply wants to wander alone in the jungle.

In Ecuador and Peru eco-tourism is such big business that it is nearly impossible to escape the clutches of the eco-tourism cartels. I had hoped that the situation would be different in less organized less visited Bolivia, but I was wrong.

…………………………………………………………….

Just south of Madidi National Park and Rurrenabaque lies the Pilón Lajas Biosphere Reserve, home to a tiny population of Mosetén, Tsimané, and Tacana people. Unlike the migrant Quechua who run Chalalán, these peoples are interrelated and truly indigenous. Though somewhat less organized, they are fully aware of the prosperity of their neighbors, and so have created a down market version of Chalalán called Mapajo which is located in an easily accessed part of the Pilón Lajas Reserve.

But I didn’t want to go to an easily accessed part of the reserve, I wanted to go deep into the wilderness to a magical place that I discovered on Google Earth, the legendary Lago Azul which the Mosetén hold sacred.

Lago Azul is small, less than a mile in length, and is surrounded by primary rainforest. What appears to be agricultural disturbance on the right of the photo above is actually crumbling rock. The rain is so intense, and the ancient deposits so worn out, that the rock surfaces erode faster than plants can grow.

The lake and surrounding jungle are believed by the Tsimané and Mosetén to be the abode of “Los Sapios”, the Wise ones. These are spirit people who enjoy an existence parallel to that of mankind. This alternative universe is a place of eternal abundance where wild game do not flee the arrow and all is well. They can see you, but you cannot see them. Any place of wild natural beauty can be inhabited by Sapios, but Laguna Azul is their home. It is wise not to trouble them.

The closer I looked on Google Earth the more completely pristine Lago Azul appeared to be, but once again I was mistaken. In 2005 a group of highland migrants somehow found the place and immediately began cutting down trees for slash and burn agriculture.

Pilón Lajas may be called a biosphere reserve, but in reality it is an Indian reservation, not for just any old Indian, but for the sole use of the indigenous inhabitants. The invading Indians came from the Andes, and they, who would disturb the spirits, were not welcome. I have read no reports of violence, but it must have been a tense encounter. Somehow they were driven away.

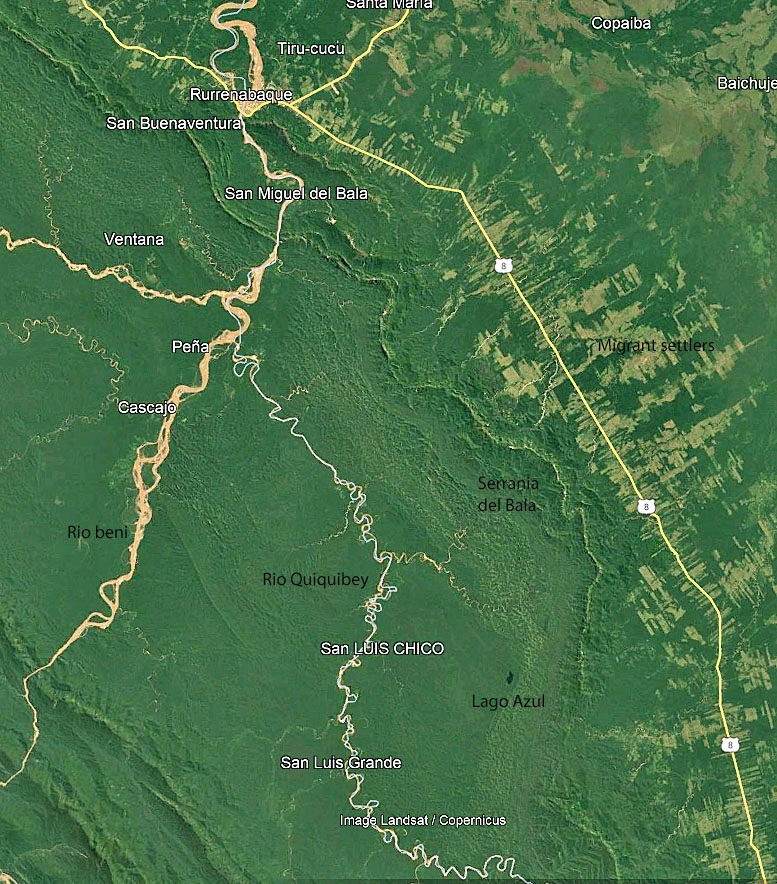

The threat is very real. In the photo below Rurre is at the top. The little dot in the lower right below San Luis Chico is Lago Azul. Route 8 is an all weather road that connects Rurre with the rest of the world. All of the many clearings that you see along the road were recently made by Andean migrants.

The wiggly line that you see just west of the clearings, and east of the Quiquibey River, is the low but formidable Serranía del Bala. This little mountain range is all that separates Lago Azul and the biosphere reserve from the hordes of hungry migrants.

The same scenario is now being played out on the grandest of scales as multitudes of redundant humans migrate in search of better lives. They come from the cradle of mankind, once verdant but now a desert. They come from peasant cultures around the world which have large families as a hedge against uncertain fate. They come from the rotting cores of cities made unlivable by crime and squalor. They drive north from their crumbling condos in the submerging city of Miami to infest my neighborhood.

They all have good reasons to want to escape the hellscape of their nativity. None of these are inherently bad people, but the mongrelization of man, and the consequent homogenization of both global culture and natural ecosystems everywhere must not be allowed to happen or what little true diversity remains, both human and natural, will be irretrievably lost.

Though I feel sorry for the poor Quechua families that flee the overpopulated highlands, I support the right of the Mosetén and Tsimané to keep out intruders even if that includes me.

……………………………………………………………….

I am not easily deterred, so I wandered around town for a few days making inquiries as to how I might ascend the Rio Quiquibey to San Luis Chico which consists of about ten huts. This provided no useful information but did lead to some ludicrous encounters.

One evening I witnessed a fine performance by stilt walking street jugglers as I had dinner in a restaurant crowded with Israeli soldiers.

It isn’t easy being a stilt walker on a busy street with numerous obstacles and deep leg breaking gutters, yet he never fell down nor dropped a club. I thought they were both great, so I tipped them a fist full of Bolivianos, about three dollars worth. They were ecstatically happy about it, so I invited them to join me for a drink.

They explained that they were performance artists from Argentina. They lived on a pittance as vagabonds, hence their happiness at my tiny tip. I asked if others in the restaurant had tipped them properly. They replied that they had received nothing, not even one measly centavo from the numerous Israelis who had watched and applauded. I could hardly believe it, what a bunch of cheapskates!

I am fond of vexing the politically correct by reminding them that stereotypes usually have some basis in fact. Everybody knows that Jews are cheap and keep nickels in their noses. I think of that as calumny, for none of my many Jewish friends are cheapskates, yet here was the proof!

I later learned that Bolivians consider all itinerant Argentinians, especially those of Italian descent, to be Gypsy swindlers who trick simple good hearted Bolivians, and here was the proof! It is always psychologically satisfying to have one’s confirmation biases confirmed!

Another widely held stereotype is that I am a dirty old man, and here is the proof.

My child bride just turned fifteen and is now officially a woman. Isn’t she lovely? The price was right. I blundered into her quinceañera while looking for a drink whereupon she dragged me up on the stage for a photo op, no doubt because I am such a handsome devil!

I followed a trail up the Rio Beni to the Pilón Lajas checkpoint where all boats are required to stop to insure that no outsiders enter the preserve without an official guide.

No one was home, but the views of the gorge of the Rio Beni were sublime.

As I walked the streets of Rurre I was constantly accosted by touts offering a jungle tour. Those few who offered tours to Pilón Lajas insisted that the Rio Quiquibey was either too low or too high to ascend, that gas for the canoe motor was unavailable, that the Sapios would be angry, or that I would surely succumb to Leishmaniasis, the scourge of the jungle. Perhaps it could be arranged, but the trip would cost a fortune, better that I should just enjoy three nights at Mapajo where I too could meet the hookey dookey bird. Eventually I gave up.

The simplest and least expensive but still overpriced option was to go to Real Beni, a village twenty minute upriver from Rurre and right around the corner from the gorge seen in the photo above. It was said to be a traditional village, but was in fact inhabited by migrant settlers who had intermarried with the Mosetén. The touts insisted that our accommodations would be set in primary rainforest full of wildlife which was of course nonsense. We were urged to bring food and school supplies to donate to the village.

We only agreed because it was a way to get out of town. I had seen a potentially interesting trail on my GPS that might provide access to the jungle. My plan was to escape as soon as we got there.

After a short ride upriver we debarked and were led to our accommodations.

The “tourist village” was located in a banana plantation, and was separated from the actual village and schoolyard by a thin screen of trees. It featured a communal kitchen where visitors could learn how to string beads, decorate pots, and cook mush. It was the same arts and crafts program I had once observed at a luxury resort in Cancun, and which is standard fare for the senile at old folks homes.

The idea was that once we had deposited our gear we would gather at the kitchen for “orientation”. Instead, the moment their backs were turned I snuck out and disappeared into the banana plantation. Ann was left behind to suffer the tender mercies of the Indian women. No one noticed I was gone until it was too late to do anything about it.

The trail was easy enough to find, after all it is on the map!

How is it that a “jungle trek” made it onto the map complete with picnic spots and campsites? You can be sure that the Mosetén didn’t do it. This is proof of outside Do-gooders in action!

The reality on the ground was quite different. As with all jungle gardens, trails went in every direction, but it was obvious that the main route followed a stream flowing down from the east.

Most tourists stop whenever they get to a stream crossing and the trail appears to end. From much experience I knew that such trails normally continue, but always further upstream and, never directly across.

Along the way I did a bit of herping. I turned over a log and found numerous wood boring grubs identical to the bess beetle larvae that I often see in rotting logs here in Florida. Other than that there was no evidence of any wildlife, not even lizards. Worst of all, the trail passed through second or third growth scrubby forest. The pristine rainforest was long gone.

There weren’t even any fish in the stream. It was obvious that the valley was periodically swept by catastrophic floods and was choked with sediment. The reason became evident when I turned a bend to behold the enormous avalanche that had devastated the valley.

For once we can’t blame this on people. As I have mentioned elsewhere, the front range of the pre-cordillera is composed of ancient granite so rotten that it often collapses just because it rains, and it always rains!

After about a kilometer and several stream crossings I met a group of tourists and their guides. They were astonished that I was in the jungle by myself, and instead of wearing long pants and rubber boots I was walking around in shorts and sandals. “How can you do that?” they asked. I pointed out that their Indian guides were also wearing sandals. Rubber boots are best when the going gets rough, but this wasn’t rough. The guides were concerned, but I told them not to worry.

Eventually I lost the trail and just continued upstream. I was delighted to see numerous morpho butterflies, and beautiful day flying Urania moths.

The further I got from the village the more animal tracks I saw. There were tracks of capybara, brocket deer, and a smallish cat such as an ocelot. One set of tracks threw me completely for a loop. They were big!

I was baffled until I got back and an old hunter said, “Es un sapo grande Señor”, a giant cane toad!

On my way back I encountered a group of boys out for a lark. They didn’t care if I had broken the rules. I was someone new to have fun with, so we made a jolly crew. Things were going well until we encountered an old woman who was greatly perturbed that I was alone. She argued that I was going to get lost or hurt. Lost following a river downstream? The kids loved the fact that I brushed off her complaints, for she probably bitched at them all the time.

As we approached the rotten log with the beetle larvae I turned to her and asked, “Want something good to eat?” The kids giggled while she looked extremely skeptical. I invited her to look under the log which I had carefully replaced. She leaned in close then sprang back in consternation when she saw the mass of wriggling larvae. I said, “What’s the matter? Don’t you like to eat these?” No! “But your grandparents ate these didn’t they?” She indignantly conceded that in the bad old days her people ate grubs, but now they were civilizados who never ate such things! The kids rolled on the ground in laughter. I was their hero because I had defeated the Old Witch!

The whole time I was gone Ann had been pestered by the village harpies who could not understand why she wasn’t troubled by my absence. “There is nothing to worry about. He often wanders off in the jungle by himself.” They didn’t believe a word of it. White men never do such things!

Ann decided to escape by wandering next door to the actual village and school to donate the school supplies that we had brought, about $50 worth of pens, paper, and antibiotic salves. The schoolteacher was extremely pleased. When Ann asked why such simple things were in short supply the teacher explained that the cooperative, which purports to to support the village, provided nothing to the school.

When I returned I was confronted by a thoroughly modern young woman who was obviously part of the problem. She was furious because I had missed lunch. I told her I wasn’t hungry but she didn’t care, I had broken the rules.

That was when I noticed an old hunter who was bemusedly watching the brouhaha. We bonded immediately when I told him I was an old hunter too, and showed him my photos of animal tracks. After that they gave up. With the old hunter on my side, along with a posse of giggling kids, I had defeated the cartel!

Over the next two days Ann and I wandered the jungle unimpeded.

As you can see, the trail isn’t very well defined. I found the missing turnoff where the picnic table is shown on the map. I can assure you that there isn’t any picnic table. From that point on the trail was only discernable by either an old Indian or an old Weazel. It appeared that no one had set foot on it for at least a year. I checked my GPS and discovered that the map was entirely wrong. So much for eco-tourism infrastructure improvements!

I was furious with myself for having fallen for a tourist trap, and for having failed to find anyone even willing to discuss, much less facilitate, a trip to the Blue Lagoon. Now that the Indians have cell phones, and take advice from Commies, it is hard to find an old warrior willing to take one last trip upriver.

The bottom line was that other than our brief little adventure at Real Beni we had failed to penetrate the jungle, so it was time to move on.

Next up, join us as we cross the Llanos de Moxos, and dive into a rabbit hole of conjecture!