By the dawn of the twentieth century there were still plenty of unknown unknowns (we never run out of those!), but very few known unknowns. These were mostly located in southwestern Brazil and adjacent parts of Bolivia.

After a somewhat disappointing sojourn in Rurrenabaque it was time to move on, in part because our visas were about to expire. As mentioned at the beginning of this series, our visas, which cost $160 (in parity with the cost of a US visa for a Bolivian) were in theory good for three months per year for ten years, yet had to be renewed every thirty days. In Santa Cruz and La Paz I had attempted to extend our visas in advance but had been denied. We were told that we had to be in a major city with an immigration office the very day of the expiration or we would be in big trouble. All this because of the equivalent trouble that US officials give anyone from Latin America who wants to visit Disneyworld.

Rurre is not a big city, but it did have an immigration office due to the influx of Israelis whose visits kept the local economy humming. All I had to do was to wake up the immigration officer who was asleep with his feet up on his desk, and bingo it was done. Though I do not condone corruption, and he had asked for nothing, I was happy to slip him a tip.

The only busses that make the long run from Rurre to anywhere else travel at night. We wanted to sightsee on our way to Trinidad, a small riverside town halfway back to Santa Cruz, so the only option was a shared taxi for the 240 mile journey. I bargained hard for the shotgun seat.

At first the graded dirt road passed through lifeless second growth jungle, the inevitable result of clearing by Andean migrants, but once we entered the edge of the savanna things got more interesting, a mix of forest, grassland, and waterways.

I watched in dismay as the miles whizzed by without any sign of wildlife until we reached the Llanos de Moxos, an area of expansive lakes and wetlands. Suddenly wildlife was everywhere! The drying wetlands were filled with wading birds such as enormous jabiru storks, caimans (think alligators), and large herds of capybaras that were so fat I thought they were pigs. Other than a lack of people, I have no explanation for why there was wildlife here but not elsewhere.

The Llanos de Moxos are generally inhospitable to human life. Soils are soggy. Flooding covers up to 60% of the land for up to 10 months; thereafter, everything bursts into flames. Just imagine the worst aspects of the Everglades and Texas combined, a great place to be a mosquito or a crocodilian, but a bad place to be either a person or a tree. Cattle ranching is the only viable occupation.

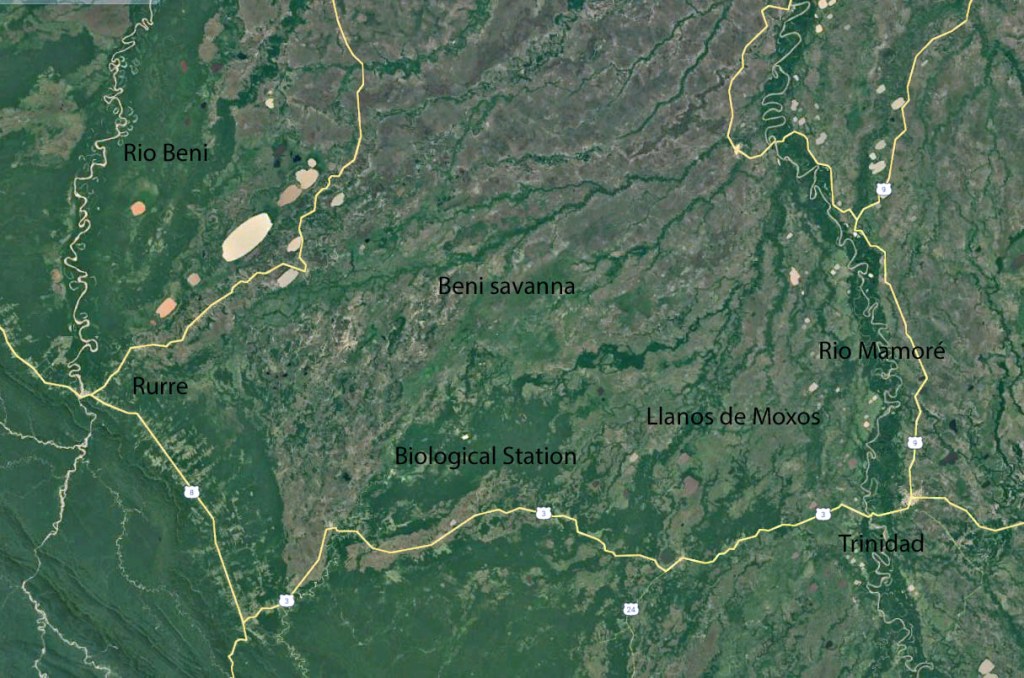

Let’s take a look at the big picture.

Forgive me dear reader for going down a rabbit hole, but there are strange and inexplicable things going on here.

Forgive me dear reader for going down a rabbit hole, but there are strange and inexplicable things going on here.

In the upper left quadrant of the image above you see what appear to be ponds filled with putrid goo. Similar but smaller ponds can be seen all over the area. (click to expand) These ponds are all relatively rectangular, and all are oriented SW to NE. I presumed that they were gold mining spoil ponds until I considered the scale. The largest one is 13 miles long, much too large to have been created by artisanal miners. The closer I looked the weirder it got.

Notice that the weird ponds are surrounded by countless relict oxbow lakes created by rivers wandering across a flat landscape over millions of years. Oxbows are by definition curved, but the putrid looking ponds are all square(ish). There are hundreds of these ponds, here but nowhere else.

The putridity is presumably due to algal blooms. Notice that right next to them are perfectly healthy black water ponds no doubt full of anacondas, caimans, and piranha. Cattle tend to frequent the savanna, so could cow pies be the culprit? Could it be ash from the seasonal fires?

Most of the square ponds are in the savanna, but how about this one which is located in terra firma forest? I was certain that it had to be gold mining since there is a village immediately to the north, but I zoomed in. No sign of disturbance other than cattle.

I researched these square lakes to no avail until I found an article that dubbed them the “Great Tectonic Lakes of Exaltation“, a highfaluting name for a putrid pond if ever I’ve heard one. It was proposed that these exalted lakes had been formed by a relatively recent large tectonic event, by which they surely meant an earthquake.

I find the idea that hundreds of square lakes of a specific orientation were created across a vast flat wetland by an earthquake to be about as likely as the works of Shakespeare being recreated by an infinite number of chimpanzees with an infinite number of typewriters pecking at random over an infinite amount of time.

There is no rational explanation for any of this. When rational explanations fail it’s time to call in the clowns, or perhaps an “expert” who can offer appealing, if implausible, “alternative” realities.

When rational explanations fail it’s time to call in the clowns, or perhaps an “expert” who can offer appealing, if implausible, “alternative” realities.

………………………………………………………………..

Archeologists are often, but not invariably, madmen. I know this because I have met many. Most are men due to the rigorous ego requirements (see Indiana Jones, et al). Some of their studies are perfectly valid and are supported by abundant evidence. Great discoveries have been made, such as Hiram Bingham’s discovery of Machu Picchu. The problem is that the world has been thoroughly explored, and there is little left to find other than perhaps a trace of DNA from a Denisovan somewhere in Siberia.

The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, so into the void step others who conjure dreamworlds from a shard of unknown provenance, or from some other tiny clue which, with enough “contextualization”, can reveal a lost civilization. Everyone, myself included, loves a lost civilization!

Everyone, myself included, loves a lost civilization!

Of all lost civilizations none can equal the legend of El Dorado. The Spanish explorers really did discover “lost” civilizations in places like Mexico and Peru. They hit the jackpot, and in a very brief time managed to loot and pillage unimaginable wealth from the new world.

Stealing gold becomes habitual, so when there was little left to steal the pious priests tortured the Indians (for their salvation of course) into revealing where the gold had come from in the first place. They had no idea, but generally speaking they pointed east toward the vast unknown Amazonian basin where it was believed that a great king known as El Dorado (the Golden One) lived in a great city where the streets were paved with gold, everyone lived for hundreds of years, the girls were pretty, and all was well. The exact whereabouts were unknown.

Over the following 500 years countless expeditions were launched in search of El Dorado. Most of the participants perished, but the few who did return were all wild eyed, bug bitten, and scrawny, still clinging to the delusion that they were on the cusp of discovery. If only I could get more funding!

Over the following 500 years countless expeditions were launched in search of El Dorado.

By the dawn of the twentieth century there were still plenty of unknown unknowns (we never run out of those!) but very few known unknowns. These were mostly located in southwestern Brazil and adjacent parts of Bolivia.

In 1913, at the pitiful end of the age of exploration, a time which coincided with the death of dreams, my personal hero Teddy Roosevelt set out in search of adventure.

Teddy had already done everything. He had been a cowboy, charged up San Juan hill, ran New York City, and was President twice. He created the National Park Service, the Forest Service, invaded and conquered the Philippines, stole the entire country of Panama to build the canal, and killed 11,400 African animals.

As a self proclaimed progressive and “trust buster” he was the only American President to ever stand up against capitalist greed. He believed in public health services, so he enacted the Pure Food and Drug Act, the predecessor to today’s U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. As a man of science you can be sure he would not have tolerated a kook like RFK, Jr. at the helm of our Nation’s health services.

After losing his third bid to become President he was old, fat, and bored, so he made the dubious decision to explore the Rio da Dúvida (River of Doubt), an unknow tributary to the Amazon in southwestern Brazil.

The Roosevelt–Rondon Scientific Expedition was intended to survey, collect specimens, and meet unknown tribes, all of which happened. It was also an utter catastrophe. His son Kermit, who joined him, went insane. Others died or were murdered.

Like Yossi the wandering Jew, they lost their dugout canoes by plunging over waterfalls. Their supplies vanished. Everyone got malaria. The parties separated, then separated again when Teddy and Kermit got lost in the jungle with no food, all the while being menaced by savage Indians. (Try to picture Trump doing this!) Eventually, more dead than alive, they were rescued by rubber tappers.

The scientific intent of the expedition was all quite proper for an old rich guy with a death wish, but you can’t fool me, I’m certain that as he lay there in the mud, feverish and starving, he dreamed of finding El Dorado. The consequences of the expedition ultimately killed old Teddy, which proves that the curse of El Dorado will never die.

I’m certain that as he lay there in the mud, feverish and starving, he dreamed of finding El Dorado.

More or less coincident with Roosevelt’s folly was that of Colonel Percy Fawcett, another lunatic adventurer in search of El Dorado.

Like some turn of the 20th century Don Quixote, Percy read so many adventure novels that they went to his head. He could no more turn back from a romantic quest than could the good Don when confronted with a windmill.

He befriended Arthur Conan Doyle, author of The Lost World, a book which greatly influenced the youthful Weazel. What’s not to love about an imaginary expedition to an unknown South American plateau inhabited by dinosaurs?

Fawcett befriended H. Rider Haggard who wrote such classics of Victorian colonial white supremacy as She who must be obeyed, about an immortal white Goddess named Ayesha who lived in a cave inside a volcano and ruled a tribe of African cannibals. He wrote the ever popular King Solomon’s Mines. Allan Quatermain, the fictional protagonist of these fanciful and very manly tales, later served as the inspiration for the Indiana Jones movie character.

In order to understand Roosevelt, Fawcett, and the Weazel one must understand the allure of such tales. Other kids played baseball and watched TV, but the Weazel eschewed such practices and preferred to read and explore. Then as now, I prefer to read first person narrative travelogues, especially those pertaining to jungle exploration. In fact, you are reading one right now!

So it was that Colonel Fawcett undertook seven expeditions into unknown parts of the western Amazon and adjacent parts of Bolivia. With every expedition he became more deluded, which is to say that he became increasingly convinced that somewhere out there waiting to be discovered was a great lost city, source of the legend of El Dorado. In order to remain respectable he deemphasized the quest for gold, and chose to call his imaginary city The Lost City of Z.

Like Roosevelt, he brought his number one son along on his final ill fated expedition in search of the Lost City of Z. Unlike Roosevelt, neither he nor his son were ever seen again. Over the years numerous expeditions set out in search of his remains. It is said by some that over 100 explorers perished in the attempt, but the number remains controversial. They may have pretended to search for Fawcett, but I know what they were really looking for, they were in search of a dream. So ended all rational hope of anyone ever finding El Dorado.

But legends die hard. In 1541 Francisco de Orellana set out in search of El Dorado. In the process he discovered and explored the Amazon river from its source, the most improbable historical event ever. As he fought his way downstream he looted and pillaged the numerous Indian villages along the banks. In doing so he spread European diseases that wiped out millions of indigenous people.

At that time nearly all the inhabitants of the Amazonian lowlands lived on the banks of rivers where they practiced slash and burn agriculture on soils periodically renewed by floods. Archeological studies reveal that such practices can lead to the formation of terra preta, dark earth full of charcoal.

From this flimsy bit of evidence archeologists concluded that the Amazon basin may once have held up to 100 million people, but other than the ubiquity of dark earth on flood levees adjacent to rivers there is little evidence that such large populations existed. The vast llanos were presumed to be devoid of people.

An archeologist with no evidence can always traffic in dreams. If there really were so many people then certainly there must have been political organization headed by wise elders with “sacred” knowledge waiting to be revealed. So it was that the legend of El Dorado was reborn, only this time with knowledge, not gold, as its goal.

It was hypothesized that this great civilization left little material evidence. After all, there are few durable materials in the Amazonian basin, neither stone nor metal, to mark the archeological record. Thatched huts, palmwood weapons, and human skeletons are ephemeral objects, but how about earthworks?

Many ancient civilizations expended inconceivable amounts of human effort to move dirt and/or rocks. It was usually a status symbol. My pile of dirt is bigger than yours! Agricultural transformation occurs on even larger scales. Anyone who has seen the vast stone terraces of the high Andes can appreciate that in pre-Columbian South America there were enough peasant laborers to literally move mountains.

Despite Fawcett’s failure to find the Lost City of Z, reports trickled in of curiously unnatural structures in the llanos such as inexplicably straight ditches, and low mounds with shards of pottery.

So it was that in 2019 a team of archeologists used helicopters to gather lidar data on the better drained portions of the llanos that lie east of the city of Trinidad. They were astonished to discover that hidden beneath the vegetation were extensive remains of mounds, platforms, ditches, causeways, and circular perimeter defenses, all made of dirt. This labor intensive work was presumably performed by the Casarabe culture which is said to have existed from ad 500 to ad 1400. Could these be the people who gave rise to the legend of El Dorado?

Imagine my astonishment to discover that these rectangular ruins are all oriented SW to NE, just like the rectangular lakes. I suppose a great earthquake did that too? (See reference to chimps, typewriters, and infinity above.)

Did these people have something to do with the square lakes? More importantly, where is the damned gold that has driven so many fools to madness?

The evidence is irrefutable. There really were large numbers of people living where people can no longer live, and they really did build monumental earthworks oriented in exactly the same direction as hundreds of inexplicably squarish lakes that bear no relationship with the adjacent landforms. El Dorado might not be real, but it gladdens the Weazel’s heart to know that some mysteries remain in our overexamined world.

El Dorado might not be real, but it gladdens the Weazel’s heart to know that some mysteries remain in our overexamined world.

………………………………………………………………………

After our lengthy and exhausting shared taxi ride across the llanos de Moxos we arrived at a ferry crossing of the mighty Mamoré river, one of the Amazon’s largest tributaries.

After crossing the Mamoré we crossed the much smaller Rio Ibare, then arrived at the wretched town of Trinidad.

As a seasoned traveler, the Weazel knows a shithole when he sees one. Unlike the friendly small cities typical of other parts of Bolivia, Trinidad emitted an ominous vibe. The streets seemed strangely empty except for thugs on motorbikes and a few mangy dogs, always a bad sign. Our hotel was located some distance from the center of town, and there didn’t appear to be any restaurants nearby. The hotel owner cautioned against walking anywhere, but I was starving so I walked downtown to discover that all the restaurants were closed and the town was devoid of colonial architecture. All the taxistas had vanished. How could there be no Tuk tuks? Where was everybody?

In my hunger I had developed a fixation on fish. Fresh fish is unknown in the Andes, but this was the Amazon, and the Ibare looked very fishy! Maybe there was somewhere to get a juicy piranha, or better still a succulent slab of catfish steamed in banana leaves?

Eventually I found a taxista sleeping on a bench. He was not pleased to be awakened, didn’t I know it was siesta time? I explained my wish for a fish and he assured me that he knew just the place. We stopped to pick up Ann, then proceeded down a narrow trash lined road far from town. I was certain we were being abducted, but eventually we arrived at Loma Suarez, a series of shack like restaurants along the Rio Ibare. For an extra fee he agreed to wait as long as necessary.

While walking around we were astonished to rediscover our shared taxi driver. He had been sullen and morose during our long morning journey, but now he was full of beer and good cheer. He recommended one of the shacks overlooking the river.

I ordered a big beer and sat back to admire the tropical scenery. The Ibare, a minor tributary of the Mamoré, is a slow muddy lowland river lined by the shacks of impoverished residents, all of whom fish for a living. Children splashed in the shallows while herons and egrets flew by. Fish, eager for oxygen, dimpled the surface. Rivers which emerge from the Andes are usually muddy, whereas those originating further downstream, and oxbow lakes disconnected from the rivers, have black water full of typical Amazonian freshwater fauna such as piranhas and caimans.

When I asked the sleepy waiter if he had any fresh fish he reacted as though I was an idiot. “That’s all we serve Señor, and you are in luck because we have fresh pacu.”

Luck indeed! The pacu is an enormous vegetarian relative of the piranha which is much esteemed for its succulent flesh. Aside from size and diet, the difference is in the teeth.

True piranha, though small, have razor sharp teeth which, as I know from experience, can bite through a steel hook. Reports that they can devour a cow in minutes are exaggerations. People often swim in piranha infested waters, but should you do so with an open bleeding wound you might get to star in your own horror movie.

The pacu on the other hand has blunt teeth similar to those of a human which are useful for chewing up fruit.

As an aside, I have a friend with a natural (non chlorinated) swimming pool into which he introduced various tropical fish, among which were a few baby pacu. He often swam naked. Over the years they got bigger and bigger until he became concerned that perhaps the pacu might inadvertently confuse his testicles with fruit. Now, lest he sing soprano, he only swims with little fish .

The repast was epic. The slab of pacu was inches thick, dripping with grease, and covered the entire plate. It was enough for four people, and we had placed two orders! I manned up, swilled beer and gobbled until I was ready to puke. I have no memory of the taxi ride back.

In the morning we were determined to find some jungle somewhere, so we asked around. Everyone agreed that there was a good jungle at a protected area located nearby at Puerto Ballivian just south of Loma Suarez. Ann’s cell phone confirmed the existence of the protected area, so we hailed another taxi.

We took the same garbage covered road we has followed the day before, only this morning there was an army of impoverished degenerates scooping up armloads of trash and whacking with machetes at the encroaching vegetation. Apparently it was the once yearly trash pickup. The labor appeared to be coerced, for the garbagemen were a woeful lot, and were overseen by men with guns. We turned off on a side road and soon reached Puerto Ballivan which was identical to Loma Suarez.

There was no way I could eat another fish, so we walked around until we found the entrance to the protected area. There was a large sign lauding all the various governmental agencies that had pretended to participate but had failed to provide any funding (proof of socialism at work), a welcome to whatever non existent tourists might wish to walk the eco-sendero (nature trail), a sign prohibiting motor vehicles, and another prohibiting the hunting of caimans.

A large trail led into the preserve. It was obvious that everyone ignored the prohibition against motor vehicles because there were numerous motorcycle tracks. The map revealed that there was an Indian village just beyond the protected area.

Despite all that, it was a beautiful trail that passed through open gallery forest along the river. The river itself was inaccessible due to tall reeds along the bank. There were morpho butterflies, a few monkeys, abundant birdlife, and the place looked perfect for snakes!

I was determined to find a snake, so wherever there was a big strangler fig I peered down into the tangled roots in hopes of an ankle nipper.

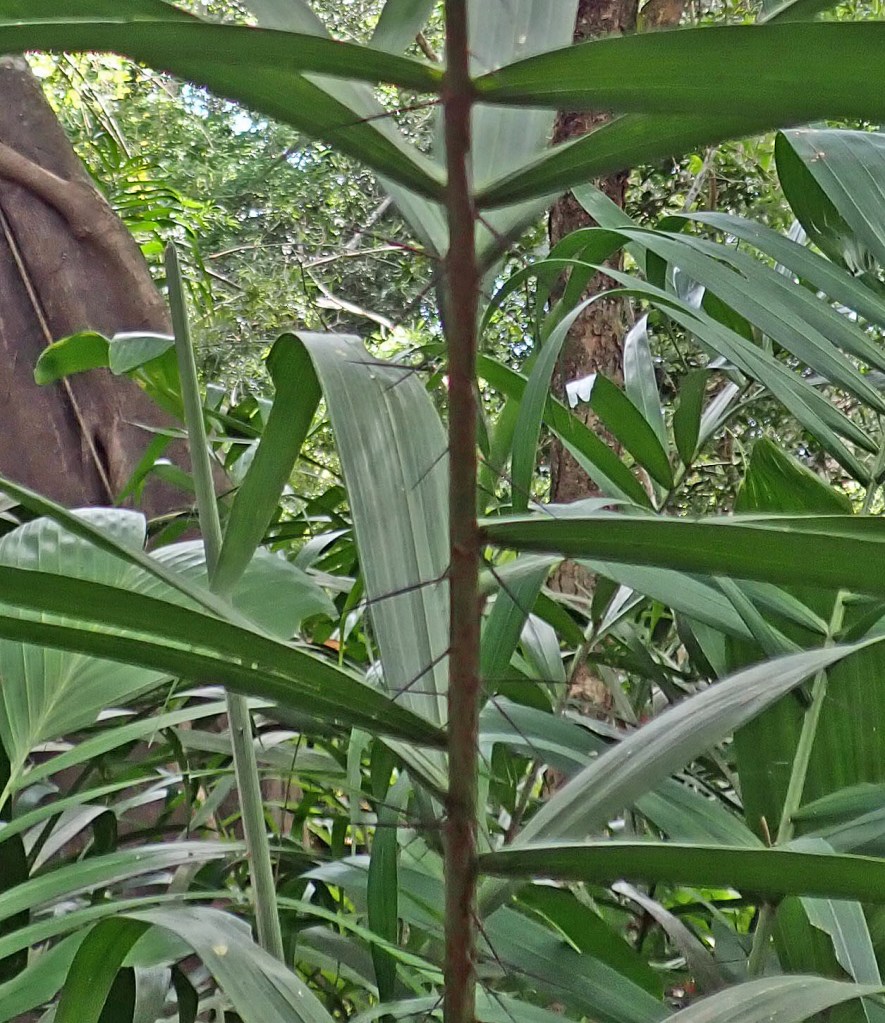

See the frilly little palms trees into which I was about to step? I paid no attention to them until I whipped out my wanger to pee. That was when I realized I was trapped, and any move would puncture me like a pin cushion!

Compared to other jungles I had seen relatively few spine palms in Bolivia. There are many species of spine palms in South America. These range from jungle giants like Acrocomia to the demonic Desmoncus which is a bullwhip like vine densely covered with spines. The slightest touch sends Desmoncus into a fury as it lashes toward your face in an attempt to bury its spines into your eyeballs.

For me the most terrifying of all are the diminutive species of Aiphanes, a pretty plant perfect for a hotel lobby in Hell. (Which is why I have installed them in several of my hotel landscapes!) The spines on the trunk and undersides of the leaves can be up to three inches long. They are so thin as to be nearly invisible, sharper than any needle, and brittle as glass. They enter your body easily and painlessly, there to shatter into pieces and fester until your gangrenous flesh either ejects them in an explosion of pus, or the sharpened point travels through your bloodstream to lodge in your heart. You can be sure that I extricated myself with great care!

After a mile or so I noticed a small side trail heading into a peninsula surrounded by an oxbow lake. The peninsula was quite hilly, a relic flood levee. It was oddly free of undergrowth on one side, and utterly impenetrable on the other. It was obvious that in antiquity enormous floods had swept the area.

I was astounded to discover that the lake looked almost exactly like a Florida lake. There were egrets, cormorants, and alligators in abundance, except that the alligators were actually caimans.

In place of our familiar live oaks there were numerous big strangler figs.

There were enormous vines of some unknown sort.

Thus far I had found no snakes, only a big snake skeleton. Suddenly Ann shouted, “Over here!” She had discovered a crocodilian graveyard. The trail we were on had been made by poachers, and the skulls of caimans were scattered about.

Back on the main trail we were accosted by a drunken Indian who wanted us to follow him to the nearby village for another drink, a bad idea, so we returned to the trailhead after a most enjoyable five mile stroll through the jungle. From Trinidad the night bus took us back to the civilized comforts of Santa Cruz.

……………………………………………………….

Next up: Join us on the final leg of our big adventure as we journey to Chiquitania, the little visited wild west (actually the east) of Bolivia. There you will see some of the most spectacular scenery of our entire trip!