Some folks just love to be miserable, so let’s visit a remote cave where a miserable hermit slowly starved to death.

…………………………………………………………….

We left the lovely little town of Chochis with its towering spire of rock, passed through the scruffy regional center of Roboré, and arrived at Santiago de Chiquitos, a tiny village founded by the Jesuits in 1754. (Refer to the previous post for more information about the Jesuits.)

To our dismay, we couldn’t find a place to stay. The inexpensive hostels were all closed due to the pandemic, but the Hotel Santiago, was still open. It was a big improvement over the chicken coop in Chochis.

From the dirt street it appeared to be yet another hovel, but at least the exterior was artfully covered in vegetation. The inside, however, was elegant! There were broad verandas, gardens, and sculpture.

The owners had incorporated traditional elements of Jesuit mission architecture including beautifully carved columns and wooden panels. Best of all, an entire pig was roasting on a spit!

The day was young, so, after a sumptuous breakfast, we asked about visiting the Cave of Juan Miserendino which had been advertised as a local attraction. The befuddled maid, the only person present, had no idea other than that it was far from town and would require a guide.

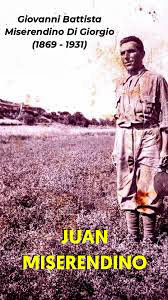

Our ideas pertaining to Juan Miserendino were as confused as those of the maid. We had read that he was a Sicilian, born in 1869, who later married a woman named Lizard, which may explain why he emigrated to Bolivia. It is said that he was a very devout man who despaired of our evil ways and took solace in a remote cave at the end of the earth where he died alone in 1931.

My Spanish isn’t very good, so I thought Miserendino meant “the miserable one”. I associated his name with “miseria”, the Latin word for misery, and with “misericord” which means to have pity in one’s heart for the miserable. It would certainly be miserable to die a lingering death in a cave, so that made sense. In fact, the word means none of that. It is an Arabic surname meaning a native of Sindh in Pakistan. Was he a Gypsy? He didn’t talk, so we will never know.

He looks miserable enough with those bloody pants. Perhaps he was a penitent who crawled around on his knees to be closer to God?

His story would be unknown were it not for the efforts of the Chiquitanean equivalent of the Chamber of Commerce who thought visits to his cave would be a great side trip for the faithful who come from all corners to visit the Jesuit mission in Santiago. The problem is that the faithful are few and getting fewer. These days more people come to Bolivia to relive the adventures of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid than to visit missions, so the story needed revision.

So arose the new legend of Juan Miserendino. In keeping with the ever popular bank robber motif, it is now said that he once worked for the Central Bank of Bolivia, from whose vaults he pilfered 100 kilos of gold bars, then fled to Roboré. From Roboré he somehow made his way to a remote cave where no one would find him. The gold is said to be buried somewhere nearby, but where? They say that on dark and stormy nights you can see his ghost roaming the wilderness to protect his hidden hoard.

None of this makes any sense, but you have to credit the C of C with having a vivid imagination. Hucksterism is an art, just ask P. T. Barnum! Allow me to ask, if you had 100 kilos of gold would you retreat to a cave where you could never spend it? The fact is that he was a miserable hermit who lived on what little food sympathetic villagers were willing to bring, and died there. His corpse was presumably a shrunken mummy by the time it was discovered.

We walked to the center of town to ask for directions, but the town was deserted. Eventually we found a few snoozing shopkeepers who told us that the cave was impossible to find without a guide. It was dangerous, and if we tried we would surely be lost!

Needless to say that did not deter the Weazel. I knew the cave was somewhere to the southeast of town, so we simply headed that way looking for trails. After numerous dead ends, and a sign pointing the wrong way, we found a barely discernable track leading through tall dry grass that was heading in the right direction.

I hate walking around in tall dry grass, especially in rural areas where livestock run loose, thereby creating a tick infested maze which goes nowhere. Aside from being ugly, the seasonally dry savanna/woodland interface is a firebomb waiting to explode. I noted the ever increasing wind and sniffed the air. So far so good, but at the slightest whiff of smoke it would be time to run.

It is important to distinguish between a biologically rich natural savanna, known as “cerrado” and a grassy weed patch. The area around Santiago was originally dry tropical forest grading into thorn scrub, but the area closest to town had been degraded by cattle into nasty grassland.

Along the way we passed enormous termite mounds that were as hard as rock. Ann thought they were rocks. The only animal that can deal with such a fortress is the giant anteater, but I searched in vain for any sign of their existence.

About a mile from town the degradation ended and we entered relatively undisturbed forest where the trail was much more easily discernable. At a fork in the trail there was a sign, arch and cave to the left, waterfall to the right.

The trail ascended a low mountain, after which we abruptly emerged into a natural short grass savanna atop a sandstone plateau. I was astonished by how much it resembled parts of Florida. Though the plant species were all different, nutrient poor sandstone derived soils and frequent fire had created an almost identical habitat.

The abrupt transition from forest to savanna can easily be seen in the tilted Google Earth image below. The red track was our hike to the cave. The blue track was a later walk to the mirador which overlooks the Tucavaca valley.

The trail became increasingly difficult to follow as it passed through areas of bare rock where the feet of occasional travelers leave no trace. In the distance we could see the promised arch. At that point I lost the trail, but Ann found it. Can you see Dr. Ann in the photo below?

We descended into a lush valley and soon found the cave. It was a big disappointment, just a shallow sandstone shelter where Juan’s family had erected a memorial plaque.

We were unable to enter due to a high fence intended to protect the many indigenous petroglyphs within. I couldn’t see them at all, but here is an image from the web. I would credit the Russian who took the photos but I don’t know how.

In the scene above people flee in terror from an attack by wild boars. Stay tuned, because shortly thereafter the same thing almost happened to us!

The trail continued, but Ann was exhausted so she stayed behind. I descended into the little valley to find a veritable paradise where a small crystalline stream ran through a grove of magnificent tree ferns. The trail ended at a natural cul-de-sac and waterfall with a sizeable sandstone cave beyond. It was a beautiful place!

The cave was more extensive than I had expected. There were a series of rooms connected by a stream, features more often associated with true solutional limestone caves. I was surprised by the lack of cave adapted biota.

I have seen sandstone caves of this sort throughout the Andes, and am puzzled by their morphogenesis. Further discussion of this phenomenon may be found in https://weazelwise.com/2023/11/16/bolivia-part-6-torotoro-the-cave/

I rejoined Ann, and we wearily made our way back. Shortly after leaving the grassy plateau we began the steep descent through the forest. Suddenly we saw the top of a nearby tree swaying back and forth. Ann whispered, “monkeys!”, but I wasn’t so sure. I motioned for her to stay behind as I crept forward. To my dismay, a short distance away was the advance guard of a large herd of white lipped peccaries, one of the most dangerous animals in South America. They were big and black, at least twice the size of a collared peccary, and appeared to weigh about 150 lbs. They are pig like, but not pigs. Their meat is esteemed, and they are often hunted. They are easy to hunt because they are unafraid, stand their ground, and sometimes attack.

We were much too close, less than thirty feet feet away. The vegetation was very dense, so we hadn’t been seen. I silently indicated for Ann to retreat, but there was nowhere to run. We crept uphill to a fallen log that gave some slight protection but not enough. If they came for us I could at least flail at them with my walking stick.

As soon as we were somewhat secure I began repeatedly yelling at the top of my lungs, “Attention all pigs! Leave immediately! This is an order! Get the Hell out of here! Now!”

“Attention all pigs! Leave immediately! This is an order! Get the Hell out of here! Now!”

As soon as I stopped yelling there was an ominous silence, then the nearest peccaries began rapidly clacking their tusks, a terrifying sound intended to intimidate whatever heard it, and to inform the rest of the herd that they were under assault. They stood their ground, a bad sign, but since they couldn’t see us they were reluctant to attack.

It soon became apparent that a much larger herd was just down the mountain, and they too began clacking their tusks. I was much relieved when the larger group fled, for the others soon followed. I will never forget the sound of the snorting, farting, clacking, and crashing as they made their way down the mountain!

I will never forget the sound of the snorting, farting, clacking, and crashing as they made their way down the mountain!

Back in Santiago we were exhausted and starving, but to our dismay the roasting pig had disappeared, and all the restaurants were closed, including the one at the hotel. The maid informed us that the pig belonged to “El Jefe” who was having a big party. We finally found a little polleria (chicken shack) and had dinner.

Back at the hotel I heard what I thought was a talented rock band practicing somewhere nearby. They were good, so despite aching feet I went out to investigate. By the time I reached the central plaza I realized that the sound was incredibly loud, and was coming from nearly a mile away. The moon was almost full, so I set out to investigate. Big shiny SUVs were heading toward the music from all quarters, very odd in a place with few cars. An elderly couple out for a stroll told me that El Jefe was a very important man from Santa Cruz, and that it was a quinceañera (15th birthday party) for his daughter. I have seen enough narco movies to know that crashing a drug lord’s private party often ends badly, so I reluctantly made my way back.

I have seen enough narco movies to know that crashing a drug lord’s private party often ends badly

The following morning I set out alone to visit the mirador overlooking the Tucavaca valley. The road was dusty and my feet were sore.

Along the way I passed the edge of the plateau we had ascended the day before.

At the pass a well worn trail led steeply upward. The way was marked with encouraging signs.

The first mirador offered a magnificent view of the Tucavaca valley far below. There was a higher overlook, but I was too tired to make the ascent.

The Tucavaca valley is, in theory, a protected area. It is extremely remote, and contains some of the last untouched dry tropical forest in the entire region. Until recently it was a haven for wildlife, but now it is beset by raging fires ignited by settlers, many of whom are Mennonites who ignore all land conservation laws in their quest to establish God’s kingdom on earth. They are relentless, and every year the fires grow worse.

At the mirador I met a beautiful dark skinned woman and her kids. She seemed altogether too elegant to be in such a place, so I asked her where she was from. She replied in English, “I’m from Aventura near Miami”. She could barely speak Spanish, so I can only guess that perhaps she was Italian, and was the wife or relative of the Jefe who had thrown the party the previous evening. Who knows who you are going to meet in the middle of nowhere?

Back at the hotel I complained about the lack of food. Was it possible that there was only one miserable polleria in the entire town, and that it was open only three days a week? The shy maid asked us to please wait. Not long thereafter we were astonished to see a formally dressed waiter appear with a tray and coffee. His manners were impeccable. Where on earth had he come from? Was it a dream? He said that dinner would be served shortly. An hour later he returned on a motorbike with a sumptuous repast featuring salted leathery steak (A Chiquitanean specialty!) along with vegetables and a salad. It was far more than we could eat. As he served us in his formal attire he held a limp and apparently defective child. He was the maid’s husband, and the food had been prepared by his grandmother. We were deeply touched, and more than happy to provide a gratuity. Civilization is where you find it.

………………………………………………………………….

Stay tuned for the final chapter of our Bolivian adventures!