Perhaps some of you have seen The Mission starring Robert De Niro. It chronicles the adventures of Jesuit priests, who, in the 1750s, attempted to penetrate the South American wilderness in an effort to subdue the fierce Guaraní, and to open a new route from the rich mines of Potosí to the Atlantic.

The original idea was to spread the Merd of Dog, I mean the Word of God, to the benighted savages. In this the gentle Jesuits were remarkably successful; but, like the Democrats of today, they overestimated the goodness of mankind, and underestimated the rapacious greed of Mammon.

Toward these ends the missionaries ascended the Paraguay river, but were effectively stopped by the Pantanal, the world’s largest wetland. Beyond the vast swamp lay the unknown lands of eastern Bolivia, home to the Guaraní, nomadic hunter gatherers reputed to be cannibals. These unknown lands would later come to be known as Chiquitania, a subdivision of the scrubby eco-region known as the Gran Chaco which covers eastern Bolivia, and adjacent parts of Brazil, Paraguay, and Argentine.

Against all odds the Jesuits succeeded. They crossed the swamp and “reduced” the Guaraní by concentrating them in settlements surrounding the newly founded missions. They were the liberals of their day, so instead of enslaving their wards they gave them clothes, taught them rudimentary agriculture, and even gave them music lessons (More on that later).

These civilizational advancements did not sit well with the more conservative elements within Catholicism, more specifically, the Portuguese who, like our current President, had no interest in education or cultural improvements of any sort. They favored either the enslavement or extermination of any and all savages regardless of whether or not they had been “saved”. Pressure against the Jesuits built until 1773 when Pope (un)Clement XIV officially sent them all to Hell. From that point on the Jesuit missions slumbered in oblivion.

All of these events occurred more than 200 years after the discovery of the silver mines of Potosí. By that time the mountain was hollow, Spain bankrupt, and well trodden paths led to Pacific ports. So it was that the Paraguay river was of little value for the transport of silver, or anything else other than cattle. That changed with the recent ascendance of the damnable soy bean, bane of Brazil. The desolate land beyond the swamp was utterly forgotten.

………………………………………………………………

I became interested in Chiquitania for two reasons, mostly because it is a forgotten place rarely visited by anyone, but also because geological maps showed carbonate deposits that might contain caves in a low mountain range known as the Serranías Chiquitanas. That proved to be a false lead. As discussed in Bolivia, part 6: Torotoro, The Cave there are very few limestone caves in Bolivia. We did visit an interesting sandstone cave near Santiago, and I subsequently discovered a most intriguing dolina near Aguas Calientes. More on all that later.

In the image above please note Chochis, Roboré, Santiago de Chiquitos, and Estancia Aguas Calientes. These are the places we will be visiting.

…………………………………………………………….

We, Dr. Ann and the Weazel, had hoped to take Bolivia’s only train from Santa Cruz to Chochis, but it arrived at 2am, so once again we had no choice but to cram ourselves into a minibus. The scenery was flat, dry, and boring, rather like much of Texas.

The entire area is dominated by Mennonites who ride around in steel wheeled horse drawn carriages feeling very smug and morally superior.

The photo above is of disobedient Mexican Mennonites who use rubber tires on their horse drawn carts, an affront to the almighty! The controversy over rubber tires caused a schism within the Mennonite community. The faithful who use nothing but wooden wheels with steel rims departed for Bolivia where they were free to breed like vermin and destroy everything in their path, all without the sacrilege of touching rubber. (That includes both condoms and tires.)

To understand the magnitude of the Mennonite infestation in South America consider the following Google Earth image which is approximately 800 miles wide.

As you can see, Chiquitania is still relatively green, whereas those areas infested with Mennonites have been sliced and diced into rectangles to grow the bad bean known as soy. Other areas were cleared for cattle. Only one generation ago almost everything in this image would have been wilderness.

Soy feeds the world, yet no one other than vegans and health food fanatics ever eats it. Aside from being hidden in every processed food, direct consumption is usually in the form of a rubbery flavorless product known as tofu. No one with the slightest aesthetic appreciation of food ever eats tofu!

Studies have shown that soy contains isoflavones which can mimic estrogen, thus contributing to the sissification of biological males around the world. Ask yourself, have you ever met a man who voluntarily eats tofu and wasn’t a sissy?

Unfortunately, the Mennonites don’t eat enough of it themselves. The damnable Anabaptists have 8 to 10 children per woman, a birthrate equivalent to the worst parts of sub Saharan Africa. Fed and financed by soy cultivation, this biblical plague is devouring the last of the Central and South American wilderness.

After leaving the agricultural lands we entered the rocky foothills of the Serranía. The slopes were adorned with Tabebuia which blooms during the austral winter.

Here is a closeup of Tabebuia I took in a park in Santa Cruz.

I was delighted to see three tayras loping across the road. Tayras are rather like wolverines with a crew cut. As fellow Mustelids they are dear to the Weazel.

The foothills gave way to sandstone mesas overlooking lush valleys. Perfect rattlesnake habitat!

As we approached Chochis we could see an extraordinary tower rising in the distance.

The Serranía is puny compared to the Andes, so we were unprepared for the grandeur of the 1500 foot cliffs that overlook the tiny town. Note that the cliff, which faces south, is almost entirely in the shade. My internal compass had a great deal of trouble adjusting to the fact that in the southern hemisphere during the austral winter the sun is far to the north.

We got off the bus to discover that no one was home. The entire town (if you want to call it a town) appeared to be deserted. There was no sign of a hotel, restaurant, or even a general store. The bus driver pointed out a ramshackled compound with a few rooms in the back, and there we found lodging.

It was a spartan but friendly place that we shared with several transient cowboys, one of whom was transporting a gigantic bull in the back of his pickup truck. The truck springs were flattened by the weight. I asked him why the bull didn’t jump out of the truck, and he responded, “I told him not to”. It seems he was a bull whisperer. I offered him a shot of rum but he demurred, saying that both the bull and his mother would prefer that he remain sober.

We were hungry but there appeared to be no restaurants of any sort. The proprietress of the hostel pointed out a house down the street with one table and two chairs on the front porch. A little hand painted sign said, “La Casona”. After much pounding on the door a kindly old woman came out. She explained that yes, it was a restaurant, but she was only open for lunch one day a week and on holidays.

She relented and fixed us a nice lunch. What we had failed to understand was that private homes in Chochis, as in many other tiny communities, are the only places where food is served, but it only happens on special occasions. Poor campesinos only eat at home if they eat at all.

Lack of food plagued us the whole time we were in Chochis. It turned out that rudimentary supplies, and even more rudimentary food, could be found at the bus station several blocks away. We didn’t know this because the bus doesn’t stop at the bus station. We stocked up on fruit, and as many ancient cans of sardines as we could find. Nobody buys canned food, so the cans were many years old and filled with sardines that had turned to mush. Praise be to Oztotl that the tienda across the street had cold beer!

There was time for a short adventure before dark, so we walked to the grassy plaza which doubled as a soccer field. At the far corner a small sign pointed to the Velo de la Novia waterfall (Bridal veil falls). The trail led across the railroad tracks to an entrance booth guarded by teenagers who charged us an outrageous 20 Bolivianos ($2.75) This, of course, was the tourist price. Even though it was a racket, the place was well kept, and the fee justified given that visitors were few and far between.

A freshly paved trail led for a kilometer up the canyon past a series of pools and small falls adorned with lovely ferns.

Along the way we were dismayed to encounter a tour group returning from the falls. They were led by a muscular young woman from Santa Cruz who berated us in English for visiting the falls without a tour guide. She went on and on about the dangers, how we would get lost (on a paved trail!), and how we could never understand the waterfall without a highly trained professional guide such as herself. We finally shut her up by explaining that we had once walked across much of Guyana without any guide.

I hope that when tour guides go to Hell my buddy Beelzebub will force them to stand at the guardrail overlooking the abyss of the seventh pit for all of eternity while reciting the same spiel over and over again.

The waterfall was quite pretty, about sixty feet tall, and kept scrupulously clean by the teenage guardians.

I was intrigued to see that the log spanning the pool featured not only the usual graffiti, but also fairly well executed carvings of squirrels, rabbits, parrots, doves, armadillos, and anthuriums. I had read that the missions of Chiquitania had a tradition of elaborate wooden carvings intended to convey biblical themes to illiterate campesinos. This was our first glimpse of wonders yet to come.

We returned at twilight to enjoy our dinner of mushy sardines. I fixed myself a stiff drink and sat for hours reading under the hostel’s one electric light. Gradually the town subsided into complete silence. South America is a generally noisy place where barking dogs, unmuffled vehicles, and wretched pop music contribute to the cacophony at all hours of the day and night, but in Chochis not a single sound disturbed the peace. I loved it!

Bruce Chatwin became famous as a travel writer because of a brief foray into South America in his youth. His resulting book “In Patagonia” was greeted with much fanfare. I recently re-read it, and was disappointed. Chatwin, like most travel writers, is more interested in people than places, whereas I am much more interested in places than people. It is always a pleasure to meet a fellow oddball such as the bull whisperer, but my primary interest is in the land itself.

So it was that when preparing for our trip to Chiquitania I read about the famous missions but failed to investigate deeply, for I have even less interest in religion that I do in people. This led me to the false conclusion that the Santuario Mariano de la Torre in Chochis was one of the ancient missions.

I expected to see a restored wooden church like this one in Concepción.

Wooden churches are the exception to the rule in South America. It is a miracle for any wooden building to survive the heat, humidity, fires, and termites of the tropics for more than 250 years, but the devotion of the Guaraní to the works of those they considered to be their saviors persisted long after the Jesuits were expelled from Bolivia.

Architecture is mankind’s most important art, and is one of my passions, so I was looking forward to admiring the architecture of the old mission, but what we found was a modern masterpiece.

……………………………………………………………….

We set out on a cold bright morning with a howling wind blowing from the south. A well paved stone road led from the plaza toward the stunning stone tower that loomed in the distance. We paid a small entry fee then began the three kilometer uphill hike to the sanctuary.

The closer we got the more impressive the tower became, a perfect monolith at least 600 feet tall.

There is a lot of erroneous information on the web about the Devil’s molar, or as the faithful call it, the Tower of David. Some describe it as made of granite. Others suppose it to be an old volcanic core. The more imaginative suppose that it was sculpted by the “ancient ones”. The reality is much more interesting.

Long before the mighty Andes were a gleam in Pachamama’s eye, long before Pangea broke up into the continents we recognize today, back when Africa and South America were one, even before there was life on earth, there was sand.

There was sand because two billion years ago the earth was barren and great storms swept the land, reducing the tallest mountains to dust. The sand formed a continuous plateau several miles thick that covered almost all of what we now call Africa and South America. Volcanic vents brought indestructible diamonds from the depths of the earth to mix with the sand, which is why African diamonds can be found in South America. Sand begets sandstone, and sandstone begets quartzite which is an extremely durable stone.

A mere 180 million years ago during the early reign of the dinosaurs the continents separated and uplift caused the ancient sandstone plateau to erode into the spectacular mesas of northern South America known as tepuis. These flat topped mountains were so remote and inaccessible that they were considered “lost worlds”. Fanciful writers like Arthur Conan Doyle even speculated that the unexplored summits were inhabited by dinosaurs. Angel falls, the world’s tallest at 3212 feet, pours down from the summit of a tepui.

Most of the tepuis are in Venezuela and Guyana, but even 1700 miles away in eastern Bolivia there are remnants of that once great plateau. Gaze in awe at a rock almost two billion years old!

At the foot of this titanic rock was The Sanctuary of the Virgin Mary, an architectural masterpiece completed in 1992 by Swiss architect Hans Roth, himself a Jesuit, who restored many of the old Jesuit missions in Chiquitania. The shrine honors the memory of those who perished in 1979 when a seemingly biblical catastrophe destroyed much of Chochis and the nearby community of El Porton.

I had expected an old wooden church, but instead I beheld a modern curving stone structure ascending the hill. It was built from the same red stone that comprises the tower. The architecture was perfectly integrated into the site, a goal that many architects profess but few accomplish.

Time for a disclaimer. For a variety of reasons including high contrast light, and the steep angle of the site, I found it almost impossible to photograph the sanctuary in a manner that does it justice. For that a drone would be necessary.

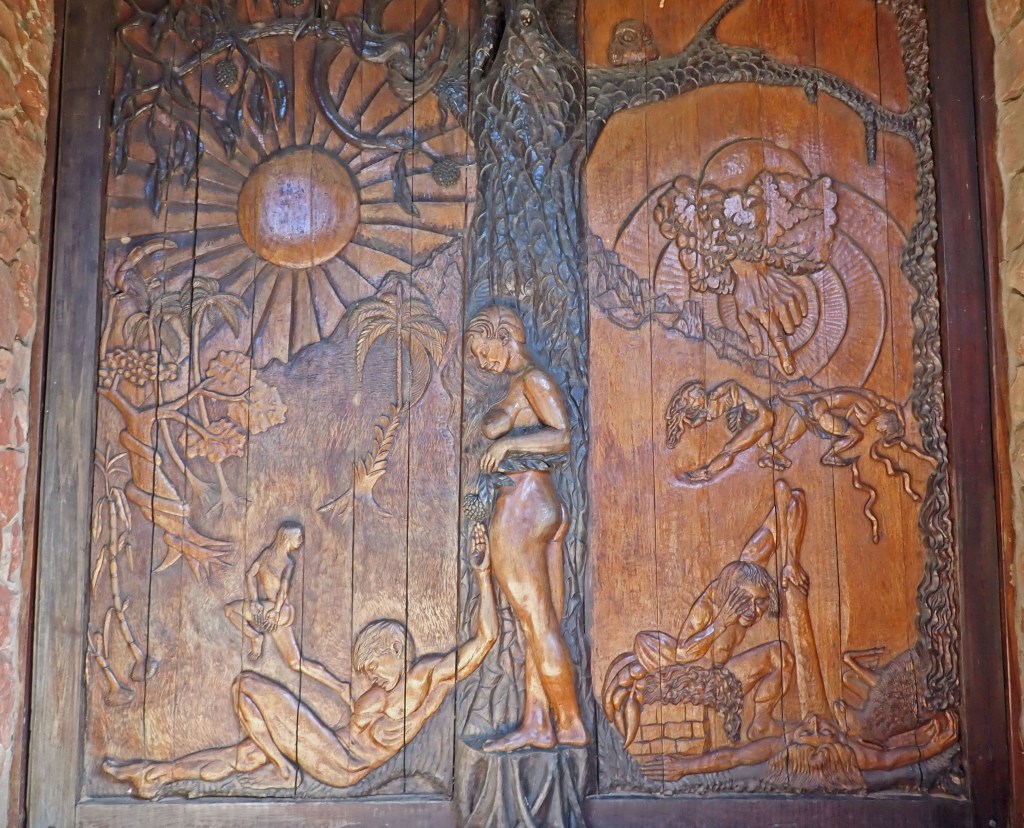

The bones are all made of stone, but everything else including the doors, columns, and interiors are lavishly adorned with carved wooden features, all of which tell a story.

Massive carved wooden columns support the roof.

Notice that traditional Andean pan pipes, violins, and guitars are represented in the columns. The Jesuits sought to “sooth the savage beasts” with music. The local Guaraní have continued that tradition until this very day.

As the story goes, “The Virgin will conceive and will give to the light a son” As you can see, he was born with a crown and useless genitalia. Even at this tender age he is already practicing his crucifixion posture. Meanwhile, the Weazel, a Hell bound atheist, lurks in the shadows.

The disaster is depicted on a series of carved wooden panels which ascend the curving stairs on the outside of the building.

On January 15, 1979, after more than a week of incessant heavy rain during the already saturated rainy season, the skies opened in a biblical deluge.

In the first panel the skies are represented by God’s water jugs, all of which are emptying into the Velo de la Novia, the beautiful little waterfall I had visited the day before. On the right the train hurries toward its rendezvous with disaster. It enters the flood but never emerges. On the left the hapless victims rush toward Chochis, but to no avail. (I have omitted several of the panels.)

Lightening and thunder rent the sky. Some say there were earthquakes, but these could not be distinguished from the gigantic boulders falling from the cliffs high above, smashing the trees, the houses, and everything in its path.

“Incessant rain. Will this be the second deluge, (the flood that heralds the end of the world)? Seek the heights, and save yourselves whoever can!”

“In the desperate struggle save yourself if you can!” Giant snakes, horses, wild boars, all were swept away! Most people simply disappeared, never to be seen again. Those who survived prayed fervently to the Virgin for salvation.

Thanks to God and the Virgin Mary help arrived from on high (In the form of Bolivian helicopters). Because most of the victims were simple peasants the death toll will never be known.

The curving stairs ended at a little grotto, then continued steeply up another set of stairs to a footpath leading to the base of the tower.

There were beautiful views of the valley far below.

Though it was growing late and our feet were tired, I could not resist a sunset stroll along the great cliff.

Fruit was hanging from the trees. The people of Chochis are rich, but they have no money.

Wealthy Yuppies from Santa Cruz often visit the sanctuary in their private vehicles, usually led by a guide, but they don’t spend a centavo in Chochis for there is nothing to buy, no place to eat, and no good place to sleep. If that were to change Chochis could become a major destination for travelers.

There was so much more to see and do. I yearned to explore the lush valley by horseback in search of pumas and serpents, but I could find no one who even knew the name of the owner of that vast estancia. Some said it was owned by the church, so go ask in Rome.

Others said that there was a magical place on the other side of the mountain where crystalline pools overlooked a moonscape of eroded rock. It was only accessible by horseback but no one knew the way.

With great reluctance we left Chochis the following day.

Stay tuned for the the next installment of our adventure as we visit Santiago de Chiquitos and the cave of the hermit!

We visited Chiquitania a couple of years ago, but I didn’t know about the movie. I’ll look for it on youtube or somewhere. Maggie

LikeLike

In the early 90s I visited the tepuis in southern Venezuela. Incredible place. Worth a visit.

LikeLike